ID Number: TQ.2016.006

Name of interviewee: Ellen Seward

Name of interviewer: Barbara Janssen

Name of transcriber: Michele Webster

Location: Ellen’s home

Address: Maders, Callington, Cornwall

Date: 18 January 2016

Length of interview: 0:46:33

Summary

Ellen’s ‘A Quilt for Howard’ was made in response to a TV interview she saw with a Chief Executive of a company who lost 658 employees in the 9/11 terror attacks on the twin towers, New York. She describes why she made the quilt, the design and construction of the appliqué quilt and what her future plans are for it. Later Ellen discusses her first quilt, her subsequent interests and influences, as well as her involvement with a textile group and some of the quilt challenges that they have undertaken.

Interview

Barbara Janssen [BJ]: ID number TQ.2016.006. Name of Interviewee Ellen Seward. Name of interviewer Barbara Janssen. Location Ellen’s home, address Maders, Callington, Cornwall. Date 18th January 2016. Many thanks for offering to talk about your chosen quilt today. I know that it was inspired, if that is the right word, by your personal response to the events in New York in 2001, so called 9/11, but before we talk about that can you briefly describe the quilt.

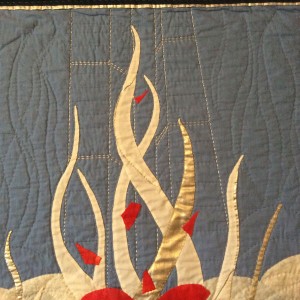

Ellen Seward [ES]: It’s rectangular. It’s about 41 inches wide and 52 inches long. Predominantly blue background, blue sky. The bottom third is blue and darker blue stripes that signify the water. The centre of the quilt is appliquéd by (coughs) excuse me, with circles of white, silver, gold, fabrics that represent clouds. From that are rising what looks like flames but they’re not actually flames, and I’ll talk about those in a minute, and then in the middle of it is a big red heart which is fractured and the pieces are just flinging off into the distance. It’s minimally quilted, there’s not a great deal of quilting on it but it’s just the picture itself that I think is what I really wanted, that was the impact that I had. There’s a very slim border round the blue, and then a deeper blue navy border framing the whole quilt.

BJ: Okay Ellen, thanks for that. It’s certainly a very dramatic quilt. Can you tell me why you felt you had to make it?

ES: Yes. On the day that 9/11 happened, the 11th September, my younger daughter Rachael had just spent the summer in New York with her, doing her gap year and we went up to Heathrow my elder daughter and I, Elizabeth and I, went up to Heathrow to collect her from the airplane. On the way back she chatted fifty to the dozen all the way down, and by the time we’d got down from Heathrow to Launceston she had exhausted herself and was falling asleep. So I turned on the car radio in time to hear a report of this happening, that had gone on in New York and by the time we’d driven the twenty minutes home, flew into the house, turned on the television in time to see the second plane go into the second twin tower and we were just stunned into silence. It was like watching a film, it was just unreal. But the biggest impact was that we had just brought Rachael back, she was on the last plane that flew out of New York [pause]. So as we watched this dreadful news report and then one of the interviewers was speaking to a gentleman named Howard Lutnick who was the chief executive of a firm called Cantor Fitzgerald and this gentleman had not gone into work that day at the top of the twin towers because he took his son to school for the first time [pause].

The interviewer was talking to Howard Lutnick who had not gone into work because he’d taken his son to school for the first time but all the rest of his firm were there and he had about seven hundred employees on the top two floors of one of the towers. Consequently all those people were killed, they had just vanished. And this ridiculous interviewer said to this poor gentleman who was almost off his seat with despair, anxiety, shock, I can’t find the words to describe, but he said to this man ‘well, how does it feel?’ and I thought you stupid person, how can a man answer that question, how does it feel to know that you have just lost part of your family ‘cos his brother and sister worked there, and seven hundred, he just was so concerned that seven hundred of his employees were gone and what was he going to do. What could he do, he didn’t know what to do, he just didn’t know what to do. He kept saying ‘I don’t know what to do’, ‘what am I going to do?’ And this stupid interviewer kept pressing him saying ‘how does it feel?’ and I thought, for crying out loud just somebody hold him, just give this man a hug [pause, crying] and nobody did [pause, microphone noise]. I just felt that this poor man needed somebody to hold him just to, just hold him and ground him because he was, you could see he was almost out of his chair, and there was nothing I could do about it. That was the big thing. We were standing in a kitchen here in England and there was nothing I could do about it. So we unpacked Rachael’s gear and were just thankful that we had her home and she had actually been round the Pentagon the day before which had also been bombed so we felt very lucky that we had her home.

And so I got to think, what can I do? And I thought, I can’t do anything. I can’t do anything but I could make a quilt. So I sat down for a few days and thought, right make a quilt. And I used wallpaper, lining paper and scribbled some thoughts down and really what was going through my mind all the time was the people who were in those two towers had gone off to work that morning like they did every morning, they would have ridden the subway, driven, however, got to work. It was about half past nine, nine o’clock I think in the morning so they were probably standing around either the water cooler or the coffee machine, or the printer or whatever. Going about their daily work and then wallop. They were just blown to kingdom come and I just had this strange, it’s a weird way to describe it but I thought, those people are rocketed into whatever is their afterlife, ‘cos there would be every religion and none amongst those people and they were just all here one minute and gone the next. And so I had visions of all these souls just rising to wherever they go [pause] and I could see, not flames, in my head I could see not flames rising but all these souls just heading off to heaven if that’s what you want to call it, but that was what was in my head. And as we watched it on the television the pictures of the huge, great billowing dust clouds against the most vivid blue sky you ever did see. But it was the fact that the glass had shattered in all the windows. It was the sunlight was just catching it, and it sparkled and if it hadn’t been for the fact that it was such a grotesque and horrible event to happen, it was beautiful. It was the most fabulous, shimmery, silvery blue sky. It was. In a way it was beautiful but it was just so horrific to, it was not true. And so I knew I had to capture some of that on this quilt and in my naivety I thought this quilt, you know, could be for Howard. But of course years and months have gone by, it’s totally the wrong thing, there’s no way anyone would want this particular quilt who has been in that position. But it was just, that was how I reacted to it. That was I couldn’t think of anything else to do but make this quilt and that’s how I worked through really my distress for this poor man Howard Lutnick, but my relief at the fact that we had our daughter home who could have been involved in this. So it was sort of a mixture of both.

So I scribbled on the lining paper and drew the clouds of smoke, the blue sky and the tongues of, that looked like flames but they’re actually in white and silver and gold and I thought New York is also called the Big Apple and so I put a huge red heart in the midst of all these flames ‘cos it was the heart of New York that was destroyed that day. And in the centre I have quilted an apple. And at the bottom of the quilt I knew that I needed to put water because there was so much water drawn from the bay that day to extinguish these flames. But of course, there’s a water between us and America so my strips of water at the bottom signify the fact that we are so closely associated with them even those it’s five thousand miles away, the Atlantic Ocean laps both countries. So I had to have some water at the bottom of it.

BJ: Thank you Ellen. It obviously is a really emotional subject for you but I’d like you to say a little bit more about your choice of your colours and the fabrics. For instance, where did you get your fabrics were what were some of the difficulties in choosing those fabrics?

ES: I wanted a blue that showed that fabulous blue sky and, like all quilters, I have a stash and rummaging through the stash didn’t produce anything really. And then one day I picked up a piece and I also had the newspaper beside me that had a photograph of the event and when I looked at the two this piece of fabric was absolutely the same colour as that in the picture so here I had it all the time. So I had my sky. I belonged to a quilting group at the time and I talked to one of them, my friend Sally Waring who is a wonderful quilter and Sally, and I wasn’t sure how to approach this. I’d drawn it out but it was actually how to construct this. And Sally’s a great appliqué person and a great piecer. Sally tried to show me a method of doing it but it was just not, it wasn’t going to work for me, not at all. So in the end I just drew round the circles, the semi-circles of the dust clouds, transferred them on to greaseproof paper for the want of a better word, I didn’t have freezer paper at that time, transferred the patterns onto greaseproof paper and then just cut round those patterns on the fabric and then just appliquéd one onto the other. And as I was doing this with the group various members would come across and say ‘is this any good?’ ‘do you think you could use this?’ And gradually, over the course of a few weeks I had amassed absolutely the right mix of pale greys, blues, whites, some that had that shimmer that just represented those shimmery glass particles. It was amazing how gradually it all just came together. And so I appliquéd one piece on top of another until I got to the buildup of the big dust clouds in the centre. And then when it came to these souls that I could see rising up to wherever I used patterns like tongues of, like you would expect, of, tongues of flame but of course I didn’t want them as flames, ‘cos they weren’t flames, these were souls of people and so I used white for that but I also used a bit of gold, I suppose it’s gold lamé and it wasn’t really quite right, it didn’t, it just didn’t look quite right and I thought ‘should I take it apart?’ and oh, I hate to take things apart so that I’ll press it, ‘cos sometimes, you know they say you can iron anything out so I pressed it and I forgot to put a piece of paper between the iron and the fabric and blow me as I took the iron off this piece quickly the iron had taken off the top surface of the shiny gold and left exactly the right piece of fabric, it was just perfect. It had dulled the gold but it was shiny enough to give a different texture. So really it, the whole of this quilt was just serendipitous I suppose. The right people had the right bits of fabric, the mistakes I made turned out to make the fabric right at that time. And then when it came to doing the sea, I’d again searched through the stash and then found a piece of fabric that looked like sea which I’d actually bought in America and had had for quite some time but there it was, it turned out to be just the perfect piece. But like, whenever you find something you never have enough. So I chopped that into strips and then interspersed the variegated blue water-like fabric with paler blues and darker blues to give the impression of the shadow of this dust cloud across the water. And so it went together. And it was amazing because I think there’s probably just enough to give it the impression so that was the centre done, then the tongues of flame but I still needed to do this heart so I had a piece of blood red fabric which I drew a big heart onto and then just cut out pieces of it and appliquéd those. I think I did that with Bondaweb, just to get them in the right position. And the pieces that I’d cut out I chopped into smaller pieces and had those going up interspersed with the tongues of the white and gold fabric as though the heart was being taken up into the heavens along with the people.

BJ: Thank you Ellen for that information. I think I agree with you about the luckiness really of the accident with the iron in getting the effect that you wanted for the gold, it’s amazing how these things happen sometimes. The quilting’s very interesting, can you tell me what you have done and why?

ES: Yes, again, I wasn’t sure how to quilt it. I decided this really didn’t mean anything unless there was some, I can’t think of the word, [pause] I knew it wouldn’t mean anything unless there was some representation of the twin towers, because that’s really what it was all about. But of course the twin towers had gone. They were no longer there. So I drew them in in pencil and then just quilted their outline in silver so the shadow of the towers are still there. And then in blue cotton again the same colour as the blue fabric for the sky I quilted more towers just rising, and dust clouds were echoed. Very simple quilting. And again along the bottom, along the sea just very simple straight line quilting just to anchor the bits together really. But the important bit to me was the silver outline of the towers.

BJ: And you mentioned earlier about the apple, the golden apple.

ES: Oh yes. Because New York is often referred to as an apple, I quilted in the shape of an apple in gold thread, so again it’s just the outline is there, not a great deal, just the significance of the apple being splintered, shattered and blown apart.

BJ: Thank you for that, Ellen. How long after the event did you begin the quilt? How long did it take you to make the quilt?

ES: I can’t remember exactly but it was quite soon afterwards because it was all still very much in my mind. And it just took about three or four months I think, picking it up and putting it down. And of course it was, as I did it, people kept asking could they do anything to help? And I couldn’t really let them do that because it was something that I had to do, I realised and in fact I just realised that more afterwards rather than at the time. That this was something that I was working through for me rather than something that other people could help with, it just had to be, it was what I could see in my head and my feelings for it and, but again, always behind it was this poor man, this poor man Howard. This was, I could not get out of my head how this man could be feeling, having lost everything and everybody. I just had to work it out myself, so I did.

BJ: 9/11 actually happened what, twelve years ago so the quilt’s obviously, you’ve had the quilt all that time, what do you intend to do with it in the long run?

ES: Well, there now, that’s the problem really. It’s not the sort of quilt that you would actually hang on your wall, it’s not big enough to be a bed quilt and it’s, the subject matter is not bed quilt material, so I’m really not sure what to do with it. I might, at the beginning it was going to be a quilt for Howard but again, thinking about it, this is, it would be totally wrong to send this to somebody who’d been affected. It would distress him even more I think if he was to have this [BJ: yeah] and so I’ve got it here and I really am not sure what to do with it.

BJ: I’m surprised that you feel that it would be totally wrong. I have a feeling that he might like to at least know about the existence of the quilt. And I know it was a while before you found out about the name of the man. Have you ever thought of finding his details and maybe sending a letter? Maybe not even sending a visual image but a letter to explain what you’ve done? And whether he would be interested in having a picture of it?

ES: I did, I actually did. [BJ: right] When I finished it I wrote to him and got no reply. And then I wrote to his sister who was also worked for Cantor Fitzgerald, virtually outlining what I’ve just said now with a picture and got no reply from them [BJ mm] so I think maybe it was too soon for them because they were probably still so affected. And then I talked to, I’m not sure whether it was, I think it was Libby [Leyman?] who came to do. It was either Libby Leyman or Marta Amundson, one of those two quilters came from America doing classes over here and I showed it to them and I think it was Libby who said before you send it to them, just write and see if it’s something they might want because it would be a shame for the work that I’ve put into it and the thought that had gone behind it for them to open it up and throw it in a cupboard because it’s… and so that’s when I really started to think, yes, it’s probably not appropriate for them, it’s probably too much of a reminder of something that they want to forget.

BJ: And yet it was meant as a hug.

ES: But it was meant as a hug.

BJ: As a, all the emotion.

ES: It was meant as a hug. [BJ yeah] But of course I’ve still got it, what I do with it I don’t know. Maybe one of these days. I showed it to, it was on exhibit in our South Hill Piecemakers Exhibition one year, and then it was in Cannington one year and the number of people who have come up and said how it had affected them, so it’s obviously, you know, affected others rather than just me and some people have said it should be in a museum, or in an art collection. I don’t know.

BJ: I don’t know about the quilt but I think there would be an interesting exercise to write an article for a magazine, have it published. I know it’s part of Talking Quilts but [ES: yup] for a wider audience, and maybe especially across the pond, just to see if there was any reaction, you know, you could write the article without the man’s name in maybe [ES: yes] sand just see if there was any reaction from that. [ES: yup] Ok. I’d like to ask you now a few questions about your quilt-making journey. When did you first start making quilts and why?

ES: I think my first quilt was actually 1971 when I was a Theatre Sister in Stonehouse Royal Navy Hospital in Plymouth. I was duty one week-end with another sister and she was quiet, we’d done all the work, she was quiet, and she was cutting out pieces of cardboard around which she was stitching fabric and I thought ‘that’s a strange thing to do!’ and so she told me what she was doing and I offered to help and she threw me a wodge of fabric and some cardboard pieces and said ‘why don’t you do some?’ So I made the dreaded hexagons! [Both laugh] Everybody starts with hexagons and I put them together and made three or four blocks and like everybody else it just grew and grew and grew but I could never come to a straight edge to stop it and when it was about single bed size I thought, ah, and I can’t remember the girl’s name, I can’t remember her name, ah, but she was going to back hers onto a sheet and then put something that she called ‘wadding’ in it and another sheet behind it. And then of course, I think she moved on to somewhere else and I still had this top of hexagons and I thought ah, sheet. So I fished out an old sheet, got some of this wadding stuff, this polyester wadding stuff, and another sheet for the back and tacked them all together. There’s no quilting on it, or very little quilting, and bound the edges, and there was my first. And it was mainly Laura Ashley offcuts.

BJ: I think we’ve all been there, that era.

ES: Absolutely, absolutely. But I vowed then never again would I do hexagons.

BJ: Yet now they’re very trendy!

ES: Now they’re trendy! [BJ: come back] and would you believe I made hexagons earlier on, later last year when I was making up a quilt, trying a quilt pattern for a quilter who writes books on quilting. One of her new patterns had hexagons on and she said would I mind doing them, however she gave me the ready cut out little templates and a glue stick to glue so there was no more stitching through the cardboard things! It was a doddle and I thought well, that’s only what, 35, no, 40 years, 40 years since I said ‘never again’ and here I am doing them!

BJ: OK, so, apart from your friend who showed you how to make these hexagons, how else have you learned about patchwork and quilting? What have been your main sources of information?

ES: I think, probably magazines, in the early days there weren’t very many but seeing some magazines. Meeting other people who, I think I went to a quilt show in London and I’ve no idea where it was, why I should be there, I can’t remember that but I remember going into a hall of some sort and there on the wall was a Durham quilt, a wholecloth quilt, and I thought oh, I’ve got one of those. When my father died and I cleared out his home at the bottom of my parent’s bed, rolled up was a quilt. And when I. They’d obviously bought a new mattress and it was too big for the bedstead so my mother had rolled up this quilt to put at the bottom to stop, to fill the space and it turned out to be a wholecloth Durham quilt.

BJ: You don’t think it was an Amy Emms quilt? [Laughing]

ES: I don’t think it was. But I remembered then that it was always referred to as Granny Nelson’s quilt. My mother’s mother was Granny Nelson. Now whether Granny Nelson had made it or whether Granny Nelson had actually paid her shilling a week into one of the clubs that were run round the turn of the century the 1800, 1900’s I’m not sure. But it’s a strippy quilt but it’s wholecloth, the pattern is strippy but the, it’s pink on one side, blue on the other, very, very faded

BJ: And you’ve still got that quilt?

ES: And I’ve still got it, I love it, I love it. I have two daughters, so I’ve two daughters and one heirloom quilt! [Both laugh] oh! I have however since acquired a second one which was made by somebody else so at least I have one quilt each, they can each have a Durham quilt but my idea was in due course to do another one. I’ve got a, made my own pattern with Lillian Hedley but I’ve yet to make it up. But I suppose my inspirations came from seeing other people’s quilts like that and that was her own design, magazines. And then I went to America many years later with David who was appointed to a post in San Diego and I went to the San Diego Quilt Show and that was [BJ laughs] amazing! Absolutely amazing. Saw fabrics there that just made your mouth water, and patterns and so I started to buy fabric and that was the beginning of [laughs] the collection! The stash.

BJ: Like a disease that you don’t want to be cured of.

ES: It’s an addiction! It’s an addiction [BJ: yeah]. Exactly! So it’s magazines, books, television programmes, I subscribe to the quilt show on the internet and joined various quilting groups and talking to other people, seeing other people’s work. And then some of these wacky ideas have come out of my own brain.

BJ: Have you got a preferred style, technique, or are you still on a journey of discovery would you say?

ES: Probably still on the journey. I’m not a precise worker, I’m very much of the ‘oh that’ll do’ school which is, I try to be better. But I think I prefer appliqué because you don’t have to make the corners meet quite so precisely as you do with piecing. So appliqué is my favourite. But having done some of the pattern testing for Pam where I had to follow a pattern and had to do piecing and had to do it correctly that sort of opened up a new little avenue for me and I thought ‘well maybe this piecing lark is not so bad after all’. So I have done a bit more piecing, and then with some of my own ideas coming through when talking to other people, talking to the girls from the Contemporary Quilt Group who said ‘why don’t you join the contemporary group because some of the things that you’re doing are more over onto the contemporary side rather than the traditional, following pattern side. And so I’ve done that. And that’s really opened up a whole new world. I’m still tentative when it comes to splashing the paint around and they dying, but I have tried it, enjoyed it, got some bits of fabric but it’s what to do with them now that I’ve made them.

BJ: Do you prefer hand or machine work or does it not matter?

ES: I’d preferred hand but as I’m advancing in years my thumbs are beginning to become a little bit stiff and so I’m going further down the machine quilting. So, bit of both really, bit of both. Depends on what the piece is, whether it needs to be hand quilted or whether I need to machine quilt it.

BJ: Where do you get your ideas for your quilts?

ES: Ah! Anywhere. Anywhere

BJ: Do they float in to your head or do get inspired by paintings or cards or [ES: yes, both] views?

ES: Everything. I read a thing the other day that said asking somebody where they get their inspiration from is like asking a bird ‘how do you fly’? [BJ laughs] [BJ: Just don’t know] Well I just do it. I just don’t know. It just. Sometimes I see, well I saw a greetings card a few years ago which I really, I just thought it was so pretty and so, that’s asking to be made into a quilt. So I wrote to the publisher who wrote to the name of the artist who had done it and got her permission to turn her design into a quilt which I did. And had the best time using hand dyed fabrics and little bits that I’d made and turned it into, and she, the artist herself, I sent her pictures and she was thrilled that somebody had done that so. But moral is you must always ask somebody’s permission if you are using a different [BJ: I agree, a lot of people don’t do that] using somebody else’s design. So yes a card or just see the fabric in the shop and think ‘ooh, oh I’d like to make that into something!’ Bring it home and then smooth it and fold it and then actually use it. But I, anyway get my inspiration from anywhere.

BJ: I know that you’ve recently formed a textile group in the West Country and you’ve set three challenges to date. Do you actually find the restriction of a challenge useful in either, you know, you’ve got a size and a date and maybe a theme or something like that. Do you find that useful?

ES: Deadlines are useful. Otherwise I tend to think things drag on and on. With a deadline, then I get it done. I was never really a great challenge person until I saw the exhibition of, in the NEC where the Loch Lomond quilt show ladies had done a Chinese Whispers they called it. And the way they had done it was one photograph sent to the first person who made a quilt, gave the photograph back, passed her quilt onto number two. She made a quilt and passed number one’s quilt back and passed hers to number three and so on down the line. Seeing how twelve ladies could make twelve different quilts from one photograph that only the first person saw just blew my mind. I’ve never been a great one for round robins where you’ve got to stitch something onto another person’s work but the fact that you could take an idea from one person and make something else, take your inspiration from that and getting such a variation, I thought was incredible. And so I asked if we could take part in the following year’s challenge that they did and got a group of friends together from the Contemporary Quilt group and outside and did the following Chinese Whispers challenge set by the Loch Lomond quilt ladies. And that was such a success and we had such fun doing it. And I think that because we were each given six weeks to do our own thing it went on for a long time but everybody seemed to enjoy it when it was finished. And so they wanted another challenge and the next one I thought rather than take the year and a half to get round the twelve people to do a simultaneous challenge and so this time I got my husband to choose a piece of music that had, just an orchestral piece of music, which he put on discs and each of the ladies in the group were given it and told to listen to it and draw, scribble, whatever. Whatever they thought of as they listened to that piece of music, draw it on a piece of paper and then make a quilt from it. Not to over think it, it was more spontaneity that we were after for this. And he didn’t tell me what it was either ‘cos I wanted to take part in it and so we did. We all listened to it in our own homes, did our own thing and after six weeks met in Barbara’s fabulous house where her husband very kindly played the piece of music for us on his violin and when we heard it, I think it was four of us out of the eleven, thought it was one thing and the others thought it was another. Some of us thought it was The Lark Ascending but it turned out to be The Girl with the Flaxen Hair by Debussy, so it was interesting that four of us thought it was the one piece and it wasn’t but Adrian played the fabulous piece of music as we unveiled the quilts and it was just a wonderful afternoon. Consequently they wanted a third one and so the next challenge was actually a poem. I took a poem and pulled out words from the poem and gave each lady just the word, nothing else. And they had to make their quilt and for this I did set a size. Obviously we wanted them all fairly manageable and this one I think was eighteen by twenty-four with again the six week deadline and they each had to interpret their word so that it would be recognizable as what it was and in due course we will exhibit the quilts along with the poem and each word will be above the quilt appropriate to that bit. So in that respect, yes, it was, I have enjoyed doing them ‘cos it, a) it gave me something to do that there was the subject already given to me or set by myself even and the deadline and then seeing the other people’s collaborations. I just love it.

BJ: I like challenges because I think they do give you, ah you know, my head is full of ideas but a challenge really makes you focus and get on with it and stop procrastinating, so it’s good.

ES: I am a great procrastinator.

BJ: I’m grateful to you for setting three challenges that I’ve taken part in (both laugh). Okay. When and where do you quilt? Where do you do your sewing?

ES: In my own home. We have a spare, well I say spare, it was a bedroom, it’s now turned into the work room. I can’t call it a studio, it’s the work room which also houses the computer and everything else. And so I work there or on the dining room table or on my lap, wherever, but usually at home. I belong to Flowerpatch Quilters in Launceston and we have the odd sewing day but we tend to have more speakers at our meetings there. Quilters’ Guild days, Contemporary Quilt days, and there are about half a dozen of us who are all Quilters’ Guild members who meet in [Coates Green Parish Hall?] Church Parlour that’s what it’s called for ‘playdays’ and there we sew and dye and paint and put the world to right and have fabulous times!

BJ: I envy you with that, it sounds like really good fun. [ES: Yes. Okay.] I want to explore a little bit more about craftsmanship and design in quilt making. What do you look for or notice in other quilts particularly?

ES: What I notice first of all I suppose is the colour. That’s the thing that strikes me. If a quilt is made of fabrics of colours I don’t like I probably don’t give it the attention it deserves. But that’s just how it is. If there are two quilts there, one with fabrics I’m not particularly drawn to and one with fabrics I really am then I’ll go to the one that I’m drawn to. So colour, I really am attracted to. And then just how it’s constructed, the accuracy of the people I admire people who can spend the time to actually make things fit, make things work and are precise. My quilts will never win prizes, I would never put mine into a competition, I would never win prizes. Having said that I did put one into NEC (laughing) and it didn’t win a prize! But I admire people who can take things apart and re-do them.

BJ: Have you got a favourite quilt or quilter?

ES: Um, [pause] yes, I think the one who really blew me away when I saw her book the first time was Libby Lehman from America. I saw her Threadplay book and what she did with her threads onto pieced backgrounds and colours was just that fabulous. I’m not a straight line person really, I’m much more of a curves and curls and freedom of movement type thing. And that’s what Libby’s were and so I really liked her work.

BJ: Okay. What do you do with the quilts that you have made?

ES: Try and find more space for them in the house! [Both laugh]. Well obviously some I’ve given away. My two girls have both got several quilts now. Make them for family members when the baby’s arrive. For various charity’s, made a number of charity quilts, and group quilts with people that I sew with. One or two up on the wall and the rest are either folded or rolled down in the work room.

BJ: Mine are over the banisters, another one for the banisters! [Laughs].

ES: Exactly, exactly.

BJ: So. Why do you think quilt making is important in your life? What sort of pros and cons or benefits or down sides has it brought to your life?

ES: Um. My mother could sew, she was not a dressmaker but she could sew beautifully and she only ever did mending and things but her hemming was so, so good and she always used to say her school teacher had said to her she should be a dressmaker. And as I’ve done my family tree I noticed that quite a number of the ladies in the generations before have been dressmakers or apprentice dressmakers or whatever so I suppose before I, without realizing it I had the ability [BJ: in the genes] It was in the genes to sew and then when I came across the fact that you could find these beautiful fabrics, these gorgeous colours, and you could cut a piece of, a square of fabric with these other pieces and other shapes and put them together and make something quite new out of that one piece of fabric, that obviously appealed to the artistic side of me and it’s a softer medium than painting. You can, you can’t wrap a painting round yourself but you could wrap a quilt round. Or you can’t wrap a painting round somebody else but you can make a quilt and wrap it round somebody else and give them warmth. I think it’s giving warmth and comfort and yet being pretty at the same time. I think, what was the question again?

BJ: I say [ES laughs] just you know, what are the benefits it may have brought to your life?

ES: People, met some fabulous people. Taken me to places in the world that I would never have gone to to see quilt shows and meet other quilters. Helped other people by doing group quilts. We’ve helped a number of charities so we’ve put, I’m using the ‘we’ here because I haven’t done any of these on my own, always been with other quilters but while you’re doing that you put the world to rights so it, the number of people who have talked through problems as we’ve sat round the quilting table, you can’t put a price on that. So the friendship, and the achievement, ‘cos when it’s finished and you look at it and somebody comes along and says ‘that’s nice’ you get a lot of satisfaction from that.

BJ: Would you say there’s been a down side at all? [ES laughs] Any,

ES: Um. Can’t get into the spare bedroom [both laugh] because there’s so many bits of fabric there but that’s not a down side really! No. [BJ: Okay.] No, I don’t think there’s a down side.

BJ: OK. Well thank you Ellen for sharing your unique quilt with us today and I hope that many other people have the chance of seeing it in the flesh or learning about it through the Talking Quilts project. [Pause]

BJ: This is Barbara Jansen speaking the day after the interview. Ellen Seward sent me the label as we forgot to discuss it at the time of the interview. The label says ‘Inspired by Howard Lutnick, CEO of Kanter Fitzgerald New York. Out of the smoke and dust rise not flames but the souls of those lost on September 11th 2001. They took to their heavens the heart of the Big Apple which was shattered that day but fear not, there is more good in this world than evil and it will mend. Ellen Seward, Callington, Cornwall, UK, 2002.