ID number: TQ.2016.002

Name of interviewee: Lesley Coles

Name of interviewer: Liz Cowley

Name of transcriber: Take 1

Location: Lesley’s home

Address: St Austell, Cornwall

Date: 19 January 2016

Length of interview: 1:16:10

Summary

Lesley has made several quilts on the theme ‘Aspects of water’, she chose to talk about her Crazy Log Cabin wallhanging quilt ‘conNECted: Aspects of Water’. The quilt was made for the first Festival of Quilts, but it is also important as she remembers making this quilt when her newborn granddaughter was poorly. She plans to give the quilt to her granddaughter when she is 21. Lesley made a Crazy Log Cabin patchwork waistcoat for her daughter in the 1970s and this led to her first quilting experiences. She talks about joining The Quilters’ Guild, being a quilt teacher (including travelling to Mongolia to teach) and the benefits of quilting. She also explains where her inspiration comes from, her quiltmaking process and her fascination with the patterns in quilts.

Interview

LiC: Okay, so I’m recording now, and I’m going to start off by listing the boring things. So, ID number is TQ.2016.002. The name of the interviewee is Lesley Coles. The name of the interviewer is Liz Cowley. The location is Region 4, and the address is St Austell, Cornwall. The date today is the 19th January 2016. Okay, and do you wanna just talk a second? So if you could tell me, your date of birth and, a… yeah, just tell me your date of birth…

LeC: I was born on the [text removed for data protection] 1949.

LiC: So, I’ll start of with, can you tell me… let’s go with, when did you make your first quilt?

LeC: I think my first quilt was in the 1980s, but I’d been doing patchwork and other practical items with it before then.

LiC: And can you tell me a bit about your first quilt that you made?

LeC: It was scrap fabric. My mother’s, mum’s dresses, my dresses, my daughter’s dresses, my sister’s dresses, but there’s… well, the scraps from making them. And then my friend contributed some of her scrap bag, and it was large hexagons. They were about three inches across, and it was all hand sewn. And it took me about four and a half years to make [laughs].

LiC: Is that the normal kind of time it takes you?

LeC: No, I’m a lot quicker than that normally, but this was a quilt that was taken to meetings, and I was babysitting circle member at the time, so it went with me wherever I went, and it was one that was cut and brought out the bag, ready to stitch, wherever I was.

LiC: And, um, what… so, what method did you use to make it?

LeC: It’s traditional English paper piecing, so the pat… patches were sewn over paper templates, which were cut out of old birthday cards and things.

LiC: So you cut out yourself? ‘Cause I know you can buy them nowadays.

LeC: Yes, they were all cut out. I drew up the template myself using my compass, and cut them all out. And as I progressed I took the patch, the papers out the centre to use again, further round [laughs].

LiC: That’s fantastic. And can you describe this quilt? So, the colour scheme, and, like…

LeC: It’s mostly purples and pinky colours, some blues, and it’s a stitched… it was appliqued onto a sheet, because I didn’t know how to finish it, and having got it to double bed size I then found there was a local craft class, and the lady very kindly said I could finish it there, and she showed me what to do to put some wadding in it, which I used polyester wadding, and I used a sheet, which I folded over the edge of the polyester wadding, and then stitched the edge of the hexagons down onto it. It hasn’t got any particular pattern to it, not like Grandmother’s Flower Garden, or anything particular. It’s just random patches.

LiC: So where, where did you first learn to quilt?

LeC: I had a friend, when I was nursery nursing, who was sewing paper piecing like this, and she showed me how to do it, and that was about ten years earlier, and I thought I’d never do it, ’cause it, I didn’t have the patience [laughs]. But then I started sewing bits of fabric together, and making bags and aprons and things, and then I decided I wanted to make a quilt.

LiC: So, have you been to any workshops or quilting courses?

LeC: Not at that point. And, at that time, early on, late 19, sort of mid to late… no, let’s start again. Mid to, sort of nineteen seventies [1970s], there weren’t, to my knowledge, any patchwork classes. I found one patchwork book in the library, which was by Alice Timmins, and I used to borrow it on regular basis, and it showed me how to do this particular type of patchwork. And then the BBC produced an, a book on patchwork, which I also got, a little paperback. And I used that, as well, quite a bit.

LiC: Fantastic. So, so you started then, and then, so did, did that spark off an interest straight away, or did you, or did you, kind of, leave it resting, come back to it?

LeC: I was always sewing, and I made my daughter a waistcoat which she was wearing to school, and at that time there was an American lady whose husband was on a sabbatical in England whose two children were in the same school. And we had a little health food shop, and Nancy used to come in the shop, and one day she said, had I made Rachel’s waistcoat? And it was appliqued pictures on it, and I said, ‘Yes,’ and she said, did I belong to The Quilters’ Guild? And I said, ‘Well, I didn’t know there was a quilters’ guild. I didn’t know there was anybody else doing anything like I was doing,’ so she introduced me to The Quilters’ Guild, which is now The Quilters’ Guild of the British Isles, and took me along to a group in Bristol called mm Bristol Patchworkers, I think, and I started going once a month to an evening where people were showing amazing quilts. So I started sewing more quilt things, than, rather than clothes, at that time.

LiC: And what, what do you remember of those meetings? What stands out in comparison to nowadays?

LeC: This amazing feeling that I could never do anything like it, and people were holding up things and saying, ‘Well, I made this last month,’ and I thought, I’ll never do that. But many years on I was doing the same sort of thing. I was doing clothing and quilt tops and things in, in about a month.

LiC: Really? In about a month which like…

LeC: Mm.

LiC: Which was, like, for somebody [talking over each other]…

LeC: Um, there’s a waistcoat here somewhere.

LiC: Oh, wow.

LeC: So, this waistcoat is Crazy Log Cabin, and pieces appliqued on top of it with 3D Flying Geese, and Prairie Points, which have, give extra texture to the surface, and tags which are stitched onto stitched string, with tags of fabric on top.

LiC: Fantastic.

LeC: And it took me about a month of sewing to do this one.

LiC: And so, can you describe the, the… so this is Crazy Patchwork?

LeC: Crazy Patchwork. Based on a Crazy Log Cabin, so instead of straight pieces they’re pieces that are wedge shape, and the centre, instead of being a square is more of a rhomboid.

LiC: And you’ve got text on here as well. Can you describe that?

LeC: I freehand stitched the text, and, um, it was a piece that I found on the little chapel, hanging in a chapel in Bleddfa in mid Wales. And it starts out, the poem, the picture of the quilt is only water taken from the well of the people, so we should… um, the well of the people. We should drink the water and, in drinking… shall we start again on that one? [both laugh] [pauses] drink the water, and it should be given back to them… and then the water should be given back to them in a cup of beauty. [reads] So they may drink and understand themselves. So, that’s not [laughs], that’s not… [talking over each other]…

LiC: No, that’s beautiful, that’s a beautiful waistcoat. And does, has anyone worn this waistcoat?

LeC: I wear it a lot, yes. It’s one of the things that I have worn… in fact, it’s beginning to wear out on the edges [both laugh].

LiC: Fantastic. So, shall we try… so you, you start at The Quilters’ Guild, and you started making quilts in the like seventies and eighties [’70s and ’80s]. Can you tell me a bit about your journey from, from then on?

LeC: So, in the early nineties [’90s] I actually joined The Quilters’ Guild, and I came across a lady who was sitting in the library one day, demonstrating a patchwork she was quilting on a patchwork quilt, and that interested me, ’cause I hadn’t really known much about the quilting side of it, apart from whole cloth quilts, which I’d found a book in the library by Elizabeth Hake, and, which I used, again, I used to take that out a lot and read it. And she was going to do a evening class, so I joined up for the evening class, and halfway through the first term she was offered a job somewhere else, so the few people that were in the group, about ten of us, decided to carry on meeting each week so we could carry on stitching our quilts. And she taught us how to use cardboard templates, cut out of cereal packets, that we’d drawn ourselves, so that we were stitching American style, what I call American style patchwork, where you cut your fabric a quarter of an inch bigger than the line that you’ve drawn for your sewing line, and then you put your pieces’ right sides together and stitch them with a straight seam. And so I was sewing a quilt… which I’m still sewing [laughs]… and, that was in the early nineteen eighties [1980s], and that was about the time I joined The Quilters’ Guild. So I went to an AGM in the mid eighteen, nineteen, err eighty six [18, 19, err, ’86], thereabouts, I think it was, with some of the Bristol quilters, and so I started doing other things. I was, I was always piecing my scraps, but I started to buy some fabric specifically for making quilts, rather than just using my scraps. I was using all sorts of other fabrics as well, to make wall hangings, and I still do that today. If I’m using, something for a wall hanging I don’t just use 100 percent cotton, I’ll use other fabrics as well.

LiC: And can you… what, what, what was this, what was this? [Looks at chosen quilt]

LeC: This was a piece that was made for a Christmas wall hanging, the challenge at one of The Quilters’ Guild days, and it’s the three que… kings, taken… the drawings I made from an image called The Magi which was a Russian orthodox poster that I’d picked up in a museum in London, and so they’re looking like orthodox priests, with the high hats, and very formal looking sort of dress. So there are satins and silks and other fabrics used in it. Lurex.

LiC: And a lot of detail, with the, in the faces and the hands and things. It’s beautiful.

LeC: Yes.

LiC: It’s beautiful. So let’s have a look at the other ones that they want us, specifically, to ask when on my own. So what, what do you think makes a good quilt?

LeC: I think that’s really difficult. I think, for me, it’s sometimes the colour, sometimes the pattern. Um, but it, it speaks to me, it, it’s, it’s almost indefinable, really. It’s like when you see an artist you like. If you like a quilt, you like it. I can appreciate good mo… workmanship. I don’t always like the colours they’ve used, so I think primarily it’s probably the colour and the pattern that they’ve used. And I like how, if you do a particular pattern, if you don’t put a sashing, a piece of fabric between the two blocks, how you get a secondary pattern occurring. So when you start looking at some patterns, they start producing second, other patterns, and I think that fascinates me as well. And that was what was happening when I met a maths teacher who was coming to some of my classes, when I started teaching patchwork in the nineteen eighties… late nineteen eighties, early nineteen nineties. She was very excited about patchwork because she could teach her students, and she had a book on tessellation, where you cut a shape into two separate shapes, and then start playing with the pieces, and it’s all to do with the same area. So, this piece was actually based on a tessellated oblong, which I’ve cut in half, with a curved piece, and then I’ve repeated that pattern across the surface. And at The Quilters’ Guild challenge in Bath in nineteen ninety eight [1998] [clears throat] they had a challenge called aspects of water, and so I did this piece. It took me about a week to do this piece, because I’d [laughs], I’d drawn up something else, and then decided I didn’t like it without a plain… with, with a plain background, so I then did the background, and then I thought, I don’t need to put the applique on it, because it’ll stand on its own. So, that was my first Aspects of Water, and then I went on to do other pieces, one of which is hanging at our church house in St Austell, and then I did Aspects of [Fire?] of Pentecost with a further push on the tessellated piece, then I’ve cut it twice to get a secondary pattern forming, as well.

LiC: So we, have we, have you, were you interested in maths, or did that interest in maths just come from…

LeC: I think the interest in maths was latent, because I’d been quite good at geometry at school, and when this particular lady said about maths and patchwork I thought, ‘Don’t say maths in front of the patchwork students, ’cause they’ll get frightened.’ But to me, it excited me, because there was so many things, that I realised I was using my maths all the time to do my patchwork designs. So I’d gone from doing very simple, traditional hexagons, doing my own applique patterns, and then stepping out to do other things… I was really playing, and doing my own thing, and then finding that other people were interested in. And, interested in what I was doing. So then, I started teaching. I was already teaching wholefood vegetarian cookery, so I started teaching patchwork… as well.

LiC: Do you find there was a correlation between the cooking and the patchwork, or are they just different?

LeC: The exciting thing about the patchwork teaching was that I was working with textiles, which I love, and sharing that love with other people. But the other thing was that I didn’t have to keep repeating my preparation. When you’re cooking, every week I had to prepare something new, and then, even if I taught it again the next year to a different group of people, I’d have to start from scratch. Whereas, at least with my patchwork, I’ve got most of my samples that keep being used again.

LiC: They didn’t get eaten [both laugh]. Sorry [talking over each other]. Now, these ones, as well, can you talk a little bit about the, so you… about the fact that you use machine quilting and, and, yeah, and what kind of, how that’s kind of influenced how you do stuff, rather than by hand?

LeC: I think I don’t have time to do everything by hand, so very quickly, although I did my hexagon quilt by hand, very quickly I was using mostly my machine. So, any quilting that I d… did originally was very basic shadow quilting, or quilting on the line of sewing in the ditch. But quickly I realised that, if I wanted to get extra texture in my work, if I used lots of machine stitching on it I could get other textures happening. And I think… I love whole cloth quilts. I think that my first memory of a quilt is when I was up in the north of England, at my granny’s, and we’d go there every year for a holiday where my mum came from, and there were whole cloth quilts there. I don’t have a, a real memory of them, just as a vague memory of them. And when I said to my mum, ‘What happened to the quilts?’ She said, ‘They got thrown out when they were worn out.’ So I think this love of texture has something to do with the very tactile nature of quilts, obviously, when I was very young, feeling the quilts.

LiC: So, so members of your family also sewed and, and made things? Can you talk about that?

LeC: My mum always sewed our clothes, but she also did tailoring classes, to make jackets and coats for us as well, and for my dad. She was really the person who taught me to sew, and I can remember sitting under her table, playing with the fa… scraps of fabric when I was very tiny. And playing with pieces of fabric was obviously [laughs] a, a delight, because there was lots of different colours. Mum liked lots of colour, so there was always good, colourful fabric. We had a scrap bag that I would delve into as soon as I could sew. I was probably about four when I made my first dolls’ clothes, and my sis… eldest sister did City and Guilds dressmaking and embroidery, so she was sewing before me, and we were taught to make our own clothes, as well, so I was making my own clothes all the way through my teens. When I couldn’t afford to buy fashionable things I was making them. And, my grandfather was a tailor, so I can remember him sitting cross-legged on the table, doing some stitching. I don’t remember exactly what [laughs]. But he, he would, he was, apparently he was a finisher of collars and, and pockets, so he would have piecework, which he would bring home, where he lived, and I can remember him sitting there, sewing.

LiC: That’s fantastic. So, it runs in the blood [laughs], it seems like. And there wasn’t ever a sense of, kind of, rebelling, going, ‘No, I’m not gonna do that, ’cause everyone else is doing that.’ It was a love of it from the start?

LeC: I would have liked to have gone to art college, but my brother was a, an artist, he drew and painted, and he used to put me down, so he said my drawings weren’t any good, and I really felt that I wasn’t any good. So, by using my textiles to do what I wanted to do creatively was an outlet, and later on, when I, after I’d done my teacher training, I was working with a student with special needs, and he was doing A Level graphic design, and the tutor was absolutely brilliant. She encouraged me to draw, and she said, ‘You could have done well with your drawing.’ So it was this thing, a bit of a regret that I never did it, but I think I found other outlets for it instead.

LiC: Right, okay, that’s fantastic, that was one of my questions I was gonna ask you, actually. So, um, so you started teaching. Does any of your, any lessons that you did, or did you… how do you find teaching, to, to help you, personally?

LeC: Oh, difficult one. I think, originally, I was just teaching basic patchwork techniques, and then people would come and do a half day, or a day with me, and then somebody said to me that they were looking for adult education tutors at St Austell College, and so I went and offered to teach some basic patchwork classes, and the rotary cutter was quite new at that time, so lots of people were buying the equipment to use a rotary cutter, and not necessarily using it properly or, or having bought it, not using it at all. And they said that they had somebody teaching patchwork, and I explained that I was teaching a modern way of doing patchwork, quick piecing, and so they took me on for a five week session, and it grew from there. I’d done, the teachers of adults certificate for City and Guilds previously for my vegetarian cookery classes, and so I carried on teaching for Adult Ed, and then, when our business was struggling in the recession in 199, early 1990s I went back to college and did a full teachers’ training course through St Austell and, Exeter University. And it was by doing that teacher training course that I realised that what I was doing was, really, what I was comfortable doing was sharing my skills with other people. But it also made me look at other techniques that I hadn’t done before ’cause they were asking to do, perhaps, Dresden Plate, which is a traditional pattern, and I’d never done it myself. So I had to then learn to do different things that they were asking me to do. But also, because I was doing a lot of my own designs, they were having my patterns to make quilts and things themselves. But it sort of grew, and I was teaching six classes a week at [laughs] night [chuckles]. Either, sort of, evening classes, or a morning class, or a whole day class, but six sessions a week.

LiC: And what, that wasn’t the plan originally?

LeC: Um, I’d, originally, when I went back to do my teacher training I thought I’d go into college and teach textiles. But I realised that the politics of education in the nineteen nineties, late nineteen nineties was not really my cup of tea, shall I say [laughs]. I wanted to be a bit freer in what I did, and I didn’t want the politics of all the paperwork. So, by…

LiC: I, I did, textiles in, I think it was ‘The Naughties’, so a bit afterwards, and it was all to do with manufacturing. There was very little creative side to doing it, so I can completely [understand] [laughs]…

LeC: Yes. Not just that side of it, but the bums on for seat funding. It wrecked Adult Ed eventually, Ad… Adult Ed isn’t anywhere as good as it was in the eighties and nineties when I was teaching most of my Adult Ed classes. So by going freelance I was able to go to different places in Cornwall, hire a room and teach up to sixteen people at time, where they would have been travelling to, perhaps, St Austell College. So I was going out to teach. And in nine… in 2004, in The Quilters’ Guild magazine, Connie Gilham, who was then the International Rep, put a little piece in about quilt teachers wanted in Mongolia, and I looked at it and thought, ‘Don’t be stupid’ [laughs]. And then I kept picking it up, and the magazine kept opening on that page. So, after a lot of thought and prayer I eventually said to my husband, ‘They want quilt teachers in Mongolia,’ and he said, ‘When are you going? So in 2006 my sister and I went for a month to Mongolia and taught at the quilt centre that, Selenga Serendash, a Mongolia lawyer had set up to help unemployed and disadvantaged women. And, we went again in 2009, where we did… I said to Selenga I wanted to do some outreach teaching, ’cause by that time she’d, she was training up teachers at the centre in Ulaanbaatar, the capital, and then using funded, funding from different departments through the government to help unemployed women, so partly the employment department, and sending her teachers out to different places in Mongolia. So I thought we would go into Ulaanbaatar, fly out to one of the other places… ’cause it’s a massive country… but she hired a van, and a man, and we went on a road trip, and we taught wherever we stopped. So she set it all up, and off we went in the van, and a teacher came with us, and I taught her when we stopped, and we stayed overnight with nomadic people in their tents, their ger, and I’m teaching them, here, how to piece silk patches to make little balls that they could give as gifts or sell. And the lady who owned this particular ger was, in her fifties, and she was watching what we were doing. It was her daughter and her daughter’s friend [coughs] who were watching and she said afterwards, ‘We won’t have to buy cheap imports to give as our gifts at New Year.’ So that was a very special time. And we taught women in the centre as well. And we taught unemployed women in different parts of the country. We travelled about 1,200 miles in total.

LiC: And Mongolia have really rich textile tradition as well, don’t they?

LeC: Their fabrics are now made in China, which is what would have been Inner Mongolia, and they import them. This was, um… and a lot of the textiles would have been made by the monks, so the women didn’t traditionally do the wall hangings and things that are in the temples, the, the monks would have done them. And there wasn’t a culture of patchwork at all. Selenga had been to America when she was a student, and had been to some patchwork classes, and when she went home she saw the women burning scraps of fabric and thought that if she could teach them what she knew they wouldn’t go cold, and they wouldn’t have to burn the fabric to, to keep them, they could make a quilt. And very quickly realised she didn’t have enough skill, so she wrote to the quilt guilds in Europe, and Connie Gilham was the only one who advertised it. We met up with some of the other Quilters’ Guild Reps at the NEC later, and introduced Selenga, [text removed for data protection]. So I was one of seven people who responded, and I was the only one who went, at that point.

LiC: So you went on your own?

LeC: No, I went with my sister, but she wasn’t a Guild member at the time. She came to Cornwall, came to some of my patchwork classes to see how I worked, and then she was my right hand woman in the classroom, and supporting me by cooking for us and things, as well.

LiC: That’s amazing.

LeC: So, they have these silk coats, which they call deel, and they use, now they’re using the scraps. This came at Christmas from Selenga. It’s a patchwork horse made out of silk scraps. They go to the women who make the deel, and get the scraps, and make things that they can sell to support the women at the centre.

LiC: Oh, that’s fantastic. And so, that just shows how much quilting can have, just, a global outreach, and a whole, kind of, community feel to it. Oh, that’s wonderful.

LeC: In, I’m not sure which year this was, but we put it in, we put a group quilt into the Festival of Quilts, and…

LiC: And, which group is this? This is…

LeC: Well, this was made by five of us, so there’s Connie Gilham from, who was the International Rep at the time that I got involved, made the first piece. Maggie Ball, who’s an, an English lady living and teaching patchwork in America, who had gone to Mongolia previous to us, and was there the year we went, and has been since to teach, made the second panel. The women in Mongolia made the third panel. I made the fourth panel, and my sister, Jane, who came with me, made the fifth panel. And it’s a map of Mongolia, and showing the ger, which is their traditional yurt tent that they live in, showing the Bactrian camel, and the mountains, and the Gobi Desert, women in traditional costume. The silk scarves, which they call [harak], which is hanging on the door of the temple, and edelweiss. In the mountains we found edelweiss as well. So this, this piece was hung at the festival of quilts after we came back. And it’s since been taken back to Mongolia, and it was taken to the embassy, and it’s been hung in various places in Mongolia. It’s been to America, so it’s travelled around the world. But it’s linking the women and textiles together, and showing that we can do amazing things with our needles.

LiC: It’s gorgeous. And where did you get the fabric from for this one?

LeC: Some of it was supplied by Strawberry Fayre. We, I sent off for the green and the blue, which is the sky. Mongolia means land of the blue sky, and often it’s, all you see is blue sky. And the green, and then bits of it were given by other people. This, the camel is made of a piece of felt, for example, ’cause they use a lot of felt in their textiles.

LiC: And this is more so, and also, with this, you can see how different people use different techniques more, as well, so, with the different, like, ratios of quilting and embroidery on the top as well.

LeC: The Mongolian women do look, a lot of embroidery, because that’s what they’re used to doing. They have quite a lot of embroidered things that they have made, but they also do crochet and other practical textile things. Mostly their skills are made to make their own clothes, and they would all have been used to having a hand cranked sewing machine, so when we went to teach the first time, the… even in the centre where Maggie Ball had taken some sewing machines from Prym Dritz, the electric machines were put to one side in preference to the hand cranked sewing machines. And in the ger they would, they came out with an old hand cranked sewing machine. A lot of them came from Russia, some of them came from China.

LiC: It’s amazing.

LeC: That’s the inside of one of the ger, and somewhere… in my pile…

LiC: [laughs] I love the way… the fact that you went from a van, I think that’s amazing. And those kind of bridges, as well.

LeC: That bridge, we weren’t allowed to go over in the van. We had to walk over.

LiC: I don’t know if I’d have even done that, to be honest…

LeC: It was scary [laughs]. It saved us about six hours round trip, though.

LiC: Yes, fair enough. And so, in this image, can you describe where you are, and what kind of environments you were teaching in over?

LeC: This is up on the top of the plateau. We’d camped overnight. In the distance, about probably a mile away across the plateau, you can see a few other tents, which belonged to a family, and the previous evening somebody had come across on his motorbike to talk to the Mongolians. I’m teaching [Dafka], the, the teacher who was travelling with us, and we’re sitting out on camp chairs with this vast open space around us, and we’d just had breakfast, and I was sitting there doing some diagrams, and showing [Dafka] a new technique. And it was cold. It had been minus seven that night, and my sister’s water had frozen in her water bottle, ’cause we were in a little [Putt?] tent.

LiC: It’s like you got into the, into the traditional [laughs] places, with the fire [talking over each other]…

LeC: Selanga had borrowed for us, um, a silk deel. The silk keeps the cold out to a certain extent. Mine was lined with a man-made fur fabric. My sister’s was lined with goats’ fur, and she said she always got the smelly one [laughs]. And it was wrapped around the waist with a, a tie, a silk sash. And then I had my neck scarf on. I had had my hat on when I was eating breakfast that morning [laughs].

LiC: And how did your hands cope in that kind of…

LeC: I did have hand warmers, and I did use them quite a lot. And during the day it got up to mid-teens, temperature wise, so it wasn’t cold during the day, usually. And we carried all our own water and food with us, but we did see some people coming to collect water, and beside this camp, about 100 yards the other way from the camp, was a deep gorge which was a, a rift from an earthquake many hundreds of years ago. And they would go down. It was about 270 feet down into the gorge to collect water from the river.

LiC: Gosh, can’t imagine that, can you? Like a little bit of cotton just [talking over each other]…

LeC: Stuck on the back of her, her deel. This was from the, the, Labour Department in Ulaanbaatar.

LiC: A [indecipherable] this certificate.

LeC: A thank you certificate. That was… and when we were travelling we didn’t have anywhere to wash our hands, we used wet wipes and hand gel. So when we came to the lake [Hosfol], which is about 26 miles long, we were able to go and wash our hands and face in the [laughs], in the lake.

LiC: Did you fi… how, how were, how did you, were you inspired by this trip when you came back home? How, how did it affect when you came back home?

LeC: I think the fact that we have so much. We find it even difficult to buy scissors… we didn’t, never found any scissors in a shop there. And when the women came to the class they often had sheep shearing scissors with them, or something. And needles were very difficult to come by, so on both of our trips, on the first trip we took sewing kits for everybody, and on the second trip we took sewing needle cases, with pins and needles in. But we went to the shop to buy pins, and we bought every packet they had, which was about four or five, and half of them were bent or rusty before they even came out the packet. So the fact that we have so much makes me very grateful. The fact that, by teaching them a simple skill, patchwork, applique, which I did over that month on two occasions, means that those women have a means of not only gaining self-worth and improving their self-image, but they have a means of making some money from their hands, and that is huge, huge thing. It’s just, well, amazing that they can do that and that, by sharing our skill like this, we can change lives.

LiC: Amazing. And they’re still out there doing it now, which is fantastic.

LeC: Yes. Selenga is employed in the… when I was there the second time we, I worked a lot with the designer that they’d employed. Maggie Ball had set up a charity through her church in America, and we helped support it, as well, and they’ve bought their own premises, so instead of working underground, in a basement, which we did the first time, they’re now up above ground, on the main street and have a shop front. They have a little shop where they sell their goods. They sell their shop, they sell their goods in the main department store, and at the airport. They employ women to bring, make things and bring them in to sell at the shop, as well, and they have employed a new designer, because the designer I worked with has left to have a baby. And some of the teachers that I taught the first time I was there earnt enough money to, to pay themselves through college, so they’ve done all sorts of other things, as well as make quilts.

LiC: So it’s been a massive enablement.

LeC: Oh, huge, huge.

LiC: It’s fantastic. Ah, wonderful. And I’m sure… and that’s, that’s probably echoing… oh God, that’s gotta be echoing, as well, through all your teaching, the enabling of people, but obviously, that’s slightly more, because it’s going from completely unemployed to then having a livelihood. But…

LeC: I think that the important thing about quilting is, when people come to class they make friends, they learn a skill, they’re using their hands, they’re working with wonderful textiles and colours, which is good for their mental health and, if they’re able to say to the person sitting next to them that they’ve got a problem, and they share it, they don’t end up in the doctor’s. Well, they don’t end up being a problem for social services, or they don’t end up being a problem for society as, as a whole. So I think sharing something as simple as sewing, and being creative is, is huge. And I’ve known people who’ve lost their husbands, and come back to class and been supported through their bereavement. They’ve lost their… I’ve had somebody lose a daughter and come through and be supported by the friends she’d made through quilting. So it’s, it’s this, little ripples in the pond make huge differences to people’s lives.

LiC: Yes. And, as well, the, is, is spending, it’s such a lovely thing that, just sitting there, and it can become so automatic, that, just talking while you’re doing it, and I think a lot of people say that they never end up,… what they do in class, they, they spend a lot less time [laughs] actually making. Means you have to unpick it afterwards, ’cause it’s not usually [laughs], not to their usual standard. But it’s the social aspect.

LeC: Yes, the social aspect, I think, is very important, mmm.

LiC: Okay, so, what do, what do, what do you do with the quilts that you’ve made?

LeC: Um, some of them get made as, specifically as presents for people. Often smaller things as well, you know, like table runners, or bags, or cushions. But also, I’ve been very involved with a lot of charity quilts, so this particular quilt here we made for a young man in, in, Romania, and we’d been involved through The Quilters’ Guild. Somebody had written to The Guild saying, ‘Remember the Red Cross quilts that were made during the war? And how about doing something for Romania?’ And this was in nineteen ninety one [1991], when the borders opened up. And a local man here had offered some equipment, and… to a local group that were going to Romania the first Easter, and they said, ‘Well, we can’t take it ’cause we haven’t got enough drivers to take all the things we’ve got,’ and he said, ‘Well, I’m a lorry driver, and I’m not employed at the moment. If you’ve got a vehicle, I can drive it.’ And he started taking loads to Romania. We made quilts, and he took them to Romania, so we ended up making in the region of 175 quilts that went to Romania. I’ve made quilts where they’ve been raffled for school projects, so, when my daughter was playing in a school concert, and a friend of mine who was the textile teacher said, ‘It’s fine, they can play a musical instrument and have a concert and raise money for the music department. I haven’t even got enough money to buy threads for my students.’ So I said, ‘Well, how about us making a quilt?’ So we did a quilt in a day with some of the GCSE students, and some of the parents, and then we got sponsored to do it during the day, and then we raffled it afterwards, and raised nearly £450.00 at that. I raised money for Roy taking the quilts and other goods to Romania by making a group quilt with people from the local churches which, again, we did in a day, and then we finished quilting it over a few weeks and raised over £400 with that. I’ve made quilts for the prem baby unit at Tredisk. Not many, but I’d like to make more, and I have got a few still, ready to be finished, because my granddaughter was very sick when she was born, and needed specialist care for the first six months of her life, so I’ve made prem baby kits, quilts, as well. And we’ve made various quilts through church for various charities, as well. So, they get a home. They have a home. I still have a few here [laughs].

LiC: Bit more than a few, but [laughs] still…

LeC: The quilt on the chair, one of my students made at a class I did on something called Stack and Whack, where you stack eight fabrics, and get the same piece cut out, and create a kaleidoscope quilt. That’s going to go to Ro… er, Mongolia. She wanted it to go to Mongolia. And the quilts that we send to Mongolia get given to the orphanage where children whose parents can’t afford to look after them, or are too ill to look after them, go to the orphanage, and they’re not allowed to leave the orphanage until they have a job. So they are trained, brought up to very high standard of education, and so we send some quilts for them occasionally. And then, when people have babies… there’s been two babies at church over the last couple of years. We’ve made quilts for them as a group. A group of us have made them.

LiC: Do you make a lot of group quilts?

LeC: Quite a few, yes. And the latest thing is that all my students who get to the age of 80, and there’s been about eight now, get a friendship quilt from the other students. We all make a block, and sign it with our names, and embroider our name, and then I put them together, and somebody in the group helps quilt them. And then they get given a friendship quilt from the group.

LiC: That’s fantastic. So, when and where do you quilt?

LeC: Here on the dining room table, m, and I am going, this week, actually, to a, a retreat, so I can have four days of sewing without anybody interrupting me [laughs].

LiC: And where, whereabouts is that?

LeC: That’s near Okehampton. And a friend of mine has organised it. So I’m going with a group of other ladies.

LiC: Just escaping life, fantastic. So, how do you go about making a quilt? Can you talk to me about, like, the process from start to, kind of…

LeC: Sometimes it’s the fabric, sometimes it’s a challenge. Sometimes I just feel I want to use a particular piece of fabric that I’ve got, or sometimes I see fabric that I… and I buy it, or sometimes I’m given fabric. The little quilts here started from my journals that, in Mongolia. I wrote a journal on my trip, so some of my thoughts and experiences have been quilted into mini quilts. They’re about, just about A4 size. So, I have to decide what size. A lot of thinking goes on first, in my head. I’m planning a quilt at the moment, and I’ve been doing that over the last three or four months. Every so often I have a little think about it, and I then put pen to paper. So I actually did a few pencil drawings yesterday for the first time, so this process is going on in my head a long time before, often, it gets out. Often it’s just a jotting on the back of an envelope, or a scrap of paper. And sometimes, if I’m doing a patchwork, I draw it up on squared paper, so I’m, I’ve got an idea of what I want, so I then start drawing it to scale on squared paper. And a lot of my sewing is organic, so I might start with a set idea and it changes as I go. This little one here is when we went for a horse ride one day, and the fabric, which is printed with horses, with images like Klimt on them. I think it’s a Laura Birch print. I bought it a long time before I used it, and I wanted to put the trees in, which are 3D Flying Geese, so they’re textured triangles, because we rode up through the hill, up the woods, through the woods, up the mountain, and when we were going up the mountain it was so steep I was worrying about how I was going to ride down again, and then I kept telling myself, just enjoy it, so this little quilt is my horse riding day, and it’s not at all as it was planned. It sort of changed as it went. I’d drawn up this sort of bit, the, the triangle mountain, but everything else changed as I went.

LiC: It’s gorgeous.

LeC: This one just, little silk one, it uses Fibonacci sizes to get the, the pattern. But it’s just fabric that was from the scrap bag at a silk shop we went to, where the lady came to my classes in Moron in the north of Mongolia, and some of the silk that my sister bought for me when we left Mongolia the first time we went into China on the trans-Mongolian train, and, we went to a silk factory to see the process of how the silk was made, so I just wanted to, to use some of the pieces. So that was a piece of material that I had a long time, with dragons woven into the silk, and I really wanted to just keep the dragons whole, I didn’t want to cut them up. And then the other pieces came out of the scrap bag. Um…

LiC: So, how would you, how would you describe your style?

LeC: Um [laughs], individual, I think. I have, I have got some quilts that are based on traditional pieces, and, there’s some Christmas quilts I have which I’ve just used traditional patterns, or extended traditional patterns, and used the block design. But a lot of my quilts are very free, from my drawings, or from my photographs, so I draw off a photograph. I might trace a bit of a photograph if I want a particular thing. And I like hand-dyed fabrics, so I do occasionally dye my own fabrics. But there’s nothing… I can’t say I do applique, or I do patchwork, or I do traditional, because there’s a mixture there. This one is, a design we called Moron-style, because we saw it on the balconies in Mongolia, and I drew it up from a photograph originally, and pieced it, and then my sister told me I’d got it wrong, ’cause I hadn’t got every bit as wide as the rest, so I had to change how I’d constructed it. But it’s using the techniques that I’ve learnt for traditional patchwork, and then extending them to allow me the freedom to do other things with it. So, for example, there’s a, a seam at an angle across here, so that I don’t have to have a seam right across the quilt, through the top of the, the, the Flying Geese piece.

LiC: It’s beautiful backing, as well.

LeC: And I often work with little size, little, small pieces, because I like to be able to, to do it on my dining room table easily, so I don’t do many big quilts. I have had a few commissions to make bigger quilts, but most of my work is smaller. These pieces, mostly, are about A4. This, the, the piece that’s at the bottom there is, is based on the paintings on the struts that support the ger. The, the photograph that was on the table.

LiC: It’s beautiful fabric, as well. And that’s appliqued on?

LeC: Yes. So I use applique quite a lot. If I can do my own drawings I do. If I’m not sure about something… we saw a wolf when we were out one day travelling, and I wasn’t sure how to get a decent image of the wolf, so what I did was download images from the internet, and then do drawings from those photographs, ’cause our photographs, the wolf was very tiny, we couldn’t, couldn’t do it. And, the background fabric behind the wolf is printed, that was, my sister found, and it, it was very much like the north of Mongolia, where there were trees up the mountains.

LiC: And that wonderful blue sky again [laughs]. So, if we go to… technology, okay, we’ve done that one. Is there anything you do not enjoy about quilting?

LeC: Repetition [laughs]. I don’t enjoy, um, repetition, so many years ago, very early on, when I worked at Bristol Children’s Hospital as a nursery nurse I worked on the unit with disturbed and, young people who had psychiatric problems, so we tried to socialise them, and one of the things we did was take them to the local art exhibitions, and the museum, and the first time I saw American quilts was in Bristol Museum. This was in, early, early nineteen seventies [1970s], and there was a little schoolhouse quilt, and I fell in love with it and thought, I’m going to do that. However, many years later, when I did my first little schoolhouse block I thought, I could never make a whole quilt of this, ’cause I couldn’t repeat this process 12, 16, 20 times [laughs]. Not for me.

LiC: And what was, what’s the process of making a schoolhouse quilt? What, what does that [talking over each other]…

LeC: It’s, it would have been… it looks like a very simplistic building with a little red roof, and a white, or, cam… calico covered walls on a coloured background, and so it would have been, all the pieces would have been cut out as squares, or oblongs, or triangles, and stitched together. And you would have had to do the same piece every block. So I didn’t like my, the idea of making a whole [laughs] schoolhouse quilt.

LiC: And that’s obviously a reflection of your style of how you, you like to do, like, the craz… like, the Crazy one, as well, and that, kind of, being creative with pattern rather than just methodically doing it.

LeC: Yes. It’s, it’s, it’s very different, because you can… everything is different. No, no two pieces are the same in Crazy Patchwork, and each block in a quilt can have the same pattern, the type of pattern, but every one is different, so when I’ve done quilts and waistcoats and things using my Crazy Log Cabin style, every little bit is different.

LiC: And so, how you use, colour and stitching fabric together, and then how you use quilting in stitching over the top? How do you kind of marry those things together, and what do you like about each of the elements?

LeC: I think, for me, it’s handling the fabric, and putting fabrics together, and then seeing whether it works or not. And because I love fabric I tend to collect quite a lot of fabric [laughs], and then every so often I’ll pull out all my blues, for example. So when I did my piece, my waistcoat is mostly bluey fabrics, and when I did the piece called Connected, Aspects of Water, it was mostly blue. When I did my tessellating Aspects of Water, which was the piece for The Quilters’ Guild, I pulled all my blues out and tried to work them together, and it’s looking… I think my surroundings inform quite a lot of my work, as well. So this piece, that is about the sea, related to St Austell Bay, which is rather grey at times, The Scilly Isles, where we were having holidays, which is quite turquoise at times, and the Cayman Islands, which is very bright turquoise at times, and so the, all those colours went into this piece.

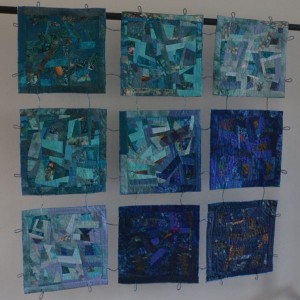

LiC: And can you describe this piece for me? ‘Cause this is really interesting.

LeC: This piece is, nine panels, and it was made for the challenge for the NEC called conNECted, with lower case letters, except for NEC being capitals in the middle of the word. And that was the challenge. And I’d seen a piece of stained glass that was several panels, and then put together with some connecting form of connection between them, so my original inspiration was the stained glass panel, and I thought, if I made separate mini quilts I could then connect them together with my tags that I make by stitching over string, and I was going, originally, to run it all the way through the whole quilt but, because it’s quite coarse, I ended up just putting it into the edge of the quilt. And to make it look cohesive I put loops of the string in the outer edge, so there’s six rows of connections going lengthwise and width-wise, to keep these nine panels together. And originally it was going to be about the sea, so the colours of the blues and the turquoises that I’ve just spoken about, and it was going to be quilted with images of ships, and other things relating to the sea. However, when I started it, my granddaughter was born with something… she was born prem, and when she was a few days old we were on the Isles of Scilly, and she was diagnosed with something called necrotising enterocolitis, which they call Nec, or NEC for short. And I started quilting my emotions into this quilt. I did some research, and we were told that Jessica might not survive, and when I did my research I realised that it was a very serious illness, and she may not survive, so all my emotions were quilted into this quilt. And all the images on it are relating to the illness, which eats the gut wall, and the bacteria that cause it, and written images… written words about the illness, and things like, only 30 percent of babies who get this survive, and it’s something like one in 300,000 babies get it, and things like that, all quilted into it. And I’ve told Jessica that she will have it when she’s 21, and she’s nearly 13. She saw me, she saw the quilt out this week and she said, ‘That’s nice, Granny,’ ’cause she’d forgotten she’d seen it previously, and I said, ‘This is the one you’re going to get when you’re 21.’ ‘Why not now?’ ‘Why not when I’m 13?’ [laughs]. So this is my, piece, I think, that I’m probably most emotional about. I, I, I would give it to her, but I wouldn’t give it to anybody else.

LiC: It’s beautiful. And so, some of the, the bacteria motifs, they’re appliqued on?

LeC: They’re appliqued on with organza, and usually it’s double organza, so that you actually get a strong image. Some of them have trailing flagella which are quilted into the fabric with multi-coloured thread, and some of them are just quilted, so some of the images are the bacteria just quilted in with the multi-coloured thread.

[long pause]

LiC: It’s so beautiful. Such an, a, such a, a, coincidence it was the NEC, and the same [laughs], the same name. So is this the St Austell panel here, by any chance?

LeC: Yes, yes. The, the, um, ones at the top are the Cayman Islands. The ones through the middle are the Isles of Scilly, and the ones at the bottom are St Austell.

LiC: And what, and do you find the sea an inspiration, then?

LeC: I find being near the sea very inspirational, and quite a lot of my quilts that I’ve done over the years have got a sea theme. They’re either fishes, or just water, or views of the sea. Quite a few pieces I’ve done, which I’ve sold since, would have had lighthouses, or coastal bits in them. But just living close to the sea, living that close to that power, is, it does make a difference, I think, to me. I love being near the sea. I love being on the beach.

LiC: And how, how’s Cor… have you always lived in Cornwall?

LeC: No, we moved to Cornwall when my children were ten and eight, so we’ve been in Cornwall longer than we’ve lived anywhere else. And I always feel at home here, although it wasn’t my natural home [laughs].

LiC: I moved here when I was two, and so therefore I can’t call myself Cornish, but I feel Cornish. I…

LeC: My granddaughter is Cornish [laughs].

LiC: My sister’s Cornish, and she likes to rub it in my face continuously. So beautiful.

LeC: So, that’s that on. Um…

LiC: And these are all your scraps, are they?

LeC: Scraps, but a lot of them have been bought.

LiC: Can you describe this for me? Kind of, size, and the colours, and everything like that?

LeC: This is another Aspects of Water, and this is, the Cayman Islands, and we have friends who live there, so we’ve been to visit them, and I learnt to snorkel there, so this is, again, it’s, it’s Crazy, but it’s a Crazy Rail Fence. So the, the pattern is strips that are wedge-shaped, and stitched together. It’s darker blues at the bottom, paler blues at the top, because when you snorkel and go under the water, when you look up the, the light shining at the top makes the water much lighter. There is, free machined, um, quilting, with all the images of the stag horn corals, and the other corals at the bottom, and a poem that our friends’ son in the Cayman Islands wrote at the top, and there’s a turtle, and it’s done in organza, and I didn’t want the edges to be very firm and finished, so I didn’t put it onto or… onto Bondaweb or anything. I just stitched the organza straight onto the quilt. So the edges are slightly fray-iy, and it did get hung at the NEC one year, and one of the comments from one of the judges is, ‘You had trouble with your raw edge applique, and I thought, no I didn’t, I wanted it to be [laughs] like that, because when you’re under the water it’s a little bit fuzzy, you don’t see the edges quite so clearly. So there’s several fish appliqued on in different coloured organzas, and they’re all machine appliqued, and then I’ve stitched extra bits of wool and other textured threads into the surface of it, as well, to create more texture. The shell of the turtle, um, it was a happy accident. It sort of doubled up when I was stitching it and I thought, that just looks like the shell of a turtle, so it’s got extra texture stitched into it to create the look of the shell of the turtle.

LiC: I love the threads you’re using in this.

LeC: I love multi-coloured threads. They, they really add another dimension to, to my work, and I use them a lot. Aurifil, and Madeira, but particularly Aurifil threads. The… they’ve got a lovely sheen to them as well. Some of them are Rayon, but most of the ones I use these days are cotton. Because it’s mercerized it’s got that extra sheen to the, to the thread.

LiC: It’s gorgeous, this detail down here is wonderful. And the backing on it, as well. I love the quilt backs. They’re always so magical to me.

LeC: I’ve pieced the back as well, because sometimes if your fabric is, that you’ve got isn’t wide enough, I often piece the back, and in this one it’s quite a large piece of batik fabric that’s got fishes on it, and I did the original outline of the fish from the batik on the back to get the organza on the front.

LiC: Fantastic. Wonderful. So where, where, [undecipherable now. So that was easy [laughs]. So, let me just see if there’s any other things that, especially in your questionnaire, I’ve highlighted [chatter].

LiC: So you said, in your questionnaire, that you’d done, taken courses with a couple of people.

LeC: Yes.

LiC: Could you talk about either of those?

LeC: For Christmas one year, when I was given some money, I decided to go to Cowslip Workshops, which isn’t so far from here, and Janet Bolton was coming, and Janet Bolton does beautiful, naïve applique, and she hand stitches, so I wanted to learn how she did some of her work, ’cause I’d admired her work for a long time. And I think what I learnt, the best thing I ever learnt from her was how to finish the edge of my quilt freehand, before I’d even made the quilt, because one of my most difficult problems, for me, was actually putting a binding on a quilt, and finishing it. So, on a lot of my later work, I use this method, where you fold the background, the back fabric over to the front of the quilt, and then you put your patchwork on top, or you put your applique on top, and then you put a piece of fabric over the top of your raw edges which you’ve folded in at the edge, and stitch it down afterwards. And this meant that I could do my open, free work without having to put a binding on a quilt. It sort of opened doors for me. Janet encouraged us to put our pieces of work on the wall, and I’d done a little piece with a frog and a, er, a fly on, er, a dragonfly on it, and called it My Bodmin Moor, and she’d encouraged us to put them on the wall so she could take a group photograph, and as I was halfway across Bodmin Moor on the way home I realised mine was still hanging on the wall at Cowslip Workshops [laughs]. It was a good excuse to go back.

LiC: It’s ama… I’ve never been there.

LeC: Oh, you haven’t?

LiC: No, it’s on my list. It’s on my list of things to do.

LeC: Oh, you have to go.

LiC: So, this is number two of LeC:. Um, so, what other things have I, er… teach your designs. Going to quilt exhibitions, have any, can, can you… any stand out for you?

1:09:07 LeC: There’s a group called South Hill Piecemakers, I think they’re called, up near, Lostwithiel, or Laun… Launceston way, somewhere in the middle of nowhere, and they set up their exhibitions in a very special way, quite unique, and they did the seasons, one year. So as you went into the hall you were directed around the hall in a particular way to go through the seasons. And their quilts are stunning. Their other things that they make with their patchwork are absolutely wonderful, and they’ve got some very talented ladies there, so there’s often a really good exhibition when you go. They don’t do it every year. I think they do it every three years, so they’re particularly good. Obviously, going to the Festival of Quilts, ’cause you’re inspired by old quilts, new quilts, all sorts, children’s quilts, and I think going to the V&A [Victoria and Albert Museum] to see the, sort of, historical quilts that were put on, three years ago, I think, three or four years ago, that was quite special, because I like looking at historical quilts. I think you have to learn about the history of quilts to take your own quilts forward.

LiC: Well, could you tell me a little bit about the history of quilts? Something that stands out for you in the history of quilts that’s kind of changed, maybe changed the way that you’ve made quilts.

LeC: I think using every scrap, and a lot of the historical quilts, even within a block, one piece would be stitched, scraps stitched together to make enough fabric, to make enough fabric for one piece to be cut out. St Fagans in South Wales had an amazing exhibition of quilts, including one made by a tailor, which I saw many years ago, and he’d stitched every little bit of wool scrap together to create enough to make this quilt, this huge quilt, which is quite well known. And that amazes me that people would have used every last scrap. And the Mongolian women doing this, where they have boxes under the table where you put your scraps. So every scrap is put into a box, and then they stitch the scraps together to make a piece big enough to cut out their strips to make their quilts from them.

LiC: Ah, that’s fantastic. So that was the exhibition. Let me just check on these ones there. Um, so why, why is quilting important in your life?

LeC: It’s just part of me, I think. I think the fact that I can create something out of very little, that I can be creative, that I can produce things that, when I look back, I think, gosh, did I do that? Is quite amazing. Because I’ve made so many friends through quilting I think, I don’t think I could live without quilting [laughs].

LiC: That’s fantastic. I think we’re gonna end it there. I think that’s… unless there’s anything else you’d like to add? Any other things?

LeC: Don’t think so, no.

LiC: Wonderful, then. I’ll press stop on that.

LeC: That the… I’ve taken Jessica’s drawings and made her a quilt. I’m waiting for it to come back from the magazine. But I’ve been writing for Popular Patchwork since the second edition, so I’ve written for every editor since it was started.

LiC: Really? And this is, so this is a picture, so…

LeC: This is Jessica’s drawings, then I in… I trace, I trace a line, I take a copy off on the photocopier, trace around it, and then I enlarge it up to the size I want, and then split it up for a pattern. So this is actually on the quilt.

LiC: That’s so cute. And has she seen this yet?

LeC: Yes, and she’s, this is when she was about six, and she says, ‘Oh, that’s so embarrassing, Granny,’ [laughs] ’cause I said would she like a copy of it? No.

LiC: No [laughs]. She’ll change her mind when she has kids, I’m sure.

LeC: And then this is the pat, Popular Patch, this is The Quilter, which is The Quilters’ Guild magazine, and, I’ve written for Ann [editor] before, and so she said she would take my mystery quilt. So, over four copies, you’ll get instructions how to do different bits, and then you’ll get told how to put it together.

LiC: Fantastic. And so this is The Quilter, is it?

LeC: Mmm.

LiC: I love this idea. It’s so adorable [laughs]. Have you got, have you got, heard of anyone else doing this? Have you put it up online, or…

LeC: Not online, no. I mean, that literally has just been published, and I, I keep the copyright, so that I can use it again if I want to.

LiC: Do you use online a lot for your, for publishing patterns or anything like that?

LeC: Well, I haven’t. But I do sell my patterns, so this, the bag that’s on the chair there, that was published in Popular Patchwork. The bag that’s in that bag was published in Popular Patchwork. But people who come to my classes will buy my patterns, as well. And when I go and do talks to WI and things like that, they, they tend to buy my patterns, as well.

LiC: My, my, the person I work for with the print production, she, um, she does, cross stitch patterns. She’s a bit hesitant to get into the online market, because once you can download a pattern, is that then stopping people then distributing that pattern as their own, or anything like that, is quite difficult. So it’s always a thing. But, saying that, if you’re get into the global market with it, if you just click download, click download… it’s brilliant. Oh, I love sampler things. And you said you dye your own fabric as well? How often do you do that?

LeC: Not as often as I did. Actually, I’ve got one pie… shall I go and get my piece from upstairs?

LiC: Yeah.