ID number: TQ.2014.001

Name of Interviewee: Nicky Ryden

Name of Interviewer: Julie Hollings

Name of Transcriber: Julie Hollings

Location: Nicky’s home

Address: Skelmanthorpe, Huddersfield

Date: 8 May 2014

Length of interview: 1:31:47

Summary

Nicky’s quilt is a celebration of 25 years of marriage and represents the history of her marriage including homes, holidays and hobbies. She did a City and Guilds course and talks about the design, fabric and technical background to making her quilt. Approximately a third of this interview explores the touchstone object, Nicky’s quilt. The remaining two thirds of the interview explores Nicky’s quilting history including starting quiltmaking, workshops and quilt qualifications, quilt and dying techniques, other quilts that she has made, The Quilters’ Guild, quiltmakers who inspire her, and her thoughts about the role of quilting for women and in the community.

Interview

Julie Hollings [JH]: Nicky, thank you for agreeing to be interviewed as part of the Talking Quilts programme. I don’t need to introduce the programme to you because you know enough about it, and I am very impressed by the quilt you have just shown me. Would you please start us off by telling us something about that quilt?

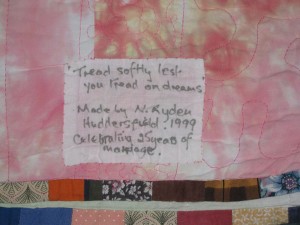

Nicky Ryden [NR]: Okay, well this quilt is one that I made as a celebration of 25 years of marriage and it was also a piece for the final stage of the City and Guilds Patchwork and Quilting which I completed in 1999, so the two things coincided and I suppose I chose this quilt because in a way it’s my attempt at something that you might say is an ‘art quilt’, it’s not based on a traditional block or anything like that, and what I was trying to do was to explore what it meant for two people to spend 25 years, well more than 25 years because we lived together for a while before we got married, living together and learning to adjust to each other, and to understand each other and to manage careers. We don’t have children so we don’t have that kind of common focus to hold us together so it was trying to explore those things that I suppose you could say ‘make a marriage’, and when I was thinking about it, what I wanted to try and do was to express in the quilt the things that were important to us, so the things that we’d shared, holidays, special places, the interests that we shared like walking and gardening and things like that. And also to acknowledge that sometimes there were difficult issues as well, often I suppose associated with both of us doing quite stressful jobs. So there were times when it wasn’t all sweetness and light. But even so, even taking those difficult times, overall we had something that was good.

So I thought about this and when you are doing City and Guilds you have to do these design sheets for your ideas and sample things, and things like that. I kind of painted two pictures, and I’m not artistic, I’m not a very good artist, but I sort of tried to represent this idea of a kind of overall impression of our marriage which is basically good and pleasant, and then one that was a bit more detailed, which included those things like the garden and hills and things like that. And one of them was quite pastelly and abstract, that was the overall impression, and the other one was more detailed and more sort of intense in colour. And then what I did was I cut up the more intense one into 25 blocks, and those blocks then ‘float’ on top of the background, which is trying to represent that concept of an overall quality of a relationship. So that was the kind of design, and I wanted to record on it in actual words names of places where we had shared special holidays and things like that, and I also wanted to record factual things like the jobs that we’d had and where we had lived because that was all part of the sum of our journey up to that time.

And I also was looking for a phrase of poetry or something like that that expressed something that I thought was important about our relationship and I found a piece that I liked from a 17th century poet called Carter that said “When I loved you and you loved me then both of us were born anew.” So there was that kind of thing about how relationships can be transformational as well. That was the design. Right. And then it was “Well how am I going to do this technically?”

JH: OK!

NR: So, I can’t remember now quite how I arrived at the decisions because it was a fair while ago, it’s about 15 years ago that I did this, but I decided that the blocks that represented the things that we were interested in, and actively did, I would do in a colour wash technique, Deirdre Amsden’s, using 1½” squares. And so I started collecting fabric to try and represent the sky, the scenery and the bottom row is gardens and things like that. And the one thing that I couldn’t find, because more than half of our married life was spent living in South Wales looking out onto one of the biggest open case mines in Western Europe, and my husband worked in the Rhondda in a college that had been associated with the mining industry, although that was all sort of closing down and I wanted something that represented that, the headgear from the pit and the terraces and cottages. And I couldn’t find anything fabric wise that did that, so I got some sort of mid brown fabric and I drew in black marker an outline of a headgear and a terrace and then I used that, I cut it up and used that in my colour wash blocks to represent the mining. So that’s this block here, and here, there’s a bit of it here. [NR and JH look at the quilt together to pick out the particular sections]. So you sort of see the windows in the houses.

JH: Yes.

NR: This was sort of meant to be part of the headgear, but it’s not very clear.

JH: And it’s almost like the seams of coal.

NR: Yes, I hadn’t thought about that but I suppose it does demonstrate that as well. And some of these fabrics, some of them are new that I had, some of them are recycled, they were from garments. This was a skirt that I had, up here in the sky there is some nightdress fabric, a petticoat, there’s one of John’s ties in here somewhere. Oh yes, that silk there.

JH: All precious pieces

NR: Some of them were precious; some of them were things that I just collected up by the way. Some of them were from other people; this was one of my mother-in-law’s dresses. So I sort of got those blocks made and then I needed to do the background on which these blocks were going to float, and I bought this piece of fine calico at a show and then I dyed it, and I wanted it to sort of represent a kind of sunrise sort of image. So we’d done some work on dying techniques and I did it by soaking the fabric in an alum solution and drying it, and then I moved all the furniture out of the dining room in the house where we were living then, and I spread a plastic sheet on the floor, and I put this piece of fabric down on the floor and then I painted it with dye, different coloured dyes. Then rolled it up in the plastic so that it was like a sort of Swiss roll kind of effect. I left it overnight so that the dye would ‘take’ and then it was rinsed through and pressed. Then it was ready.

So the colour wash blocks are actually sewn in on reverse appliqué, so I’ve stitched them onto the back of the fabric then I’ve cut away a window to show the colour wash effect, then satin-stitched it round. And I very carefully matched the colour of the satin stitch to the colour of the background.

JH: Yes, none of this has happened by accident!

NR: [Laughing] And then it has an internal sort of framework, which is free-motion quilted, and I’ve used close stitched stippling to highlight the lettering that I wanted to put on it, which records our names and the dates of our marriage and the date of our 25th anniversary. And then I put on the outer borders, where I discovered that I’d miscalculated with my measurements somewhat and it wasn’t quite long enough, so on both of the long sides I had to inset a piece that was actually cut from when I had inset the blocks. So I had to inset these pieces to make the sides long enough!

JH: And looking at that, one wouldn’t know.

NR: But actually it’s quite a nice feature now.

JH: Yes.

NR: And then I bound it with blocks that I had left over from the colour wash because I had made more than I needed, which I joined together. And because I couldn’t actually do a proper mitred corner because these were 1½ inch blocks that were seamed together at inconvenient moments, I sort of made the corners rounded by actually drawing round a quarter of a dinner plate I think! [Laughing] And then I wrote in different parts of the border things that I wanted to record like our places of work, the addresses of our houses, so this was our first flat that we rented as students and that we lived in for three or four years after we’d finished at university. And then this which sounds very posh, Le Chateau in Broughton, in South Wales, was actually a tiny little cottage, single storey, nothing chateau-like about it at all, that we rented. And then that was our first house in St Peter’s Close, and that was our second house in Huddersfield, where we were living at the time that I made this quilt.

And then down the left hand side I recorded places that were special to us as holiday destinations, Moscow to Irkutsk was on the train, on the train to Khaberosk. Places in Wales that we went and stayed in. The Lake District which is very special. For a lot of years we went back regularly every year to Buttermere. These are Eskdale, Muncaster Fell, walks that were special.

So that’s my quilt. And we use it on our bed as a bedspread. Sometimes in the summer when it’s hot and we don’t actually need a duvet we use it as a blanket. And it’s faded! A couple of the patches are fraying! But it’s, it’s … it’s special.

JH: It certainly is. So much detail, so many techniques, there is so much learned information, learned skill that has gone into it.

NR: Yes, well I guess I wouldn’t have been as ambitious to include so many techniques if it hadn’t been for the requirements of the City and Guilds. Oh and the backing, this is space-dyed, which is quite simple. You just damp your fabric and put it in a tray and drop your dye on it and it spreads, but this was actually a sheet that my husband’s grandmother gave to us when we set up home together.

JH: Right.

NR: And it seemed appropriate that it should be recycled in that way.

JH: Brilliant. So much nostalgia.

NR: Yes, it’s a real kind of memory thing. And it’s quilted with polyester thread which I don’t really like because it’s… I mean it’s worked, but as a thread to quilt with it’s not one I would choose to use but it meant that I didn’t have to keep changing colours, you know, that I could go across all of the blocks and the thread would take up the background colour that it was travelling over, and it’s sort of random quilted. No particular pattern.

JH: Amazing, amazing. And you’ve told me in that very in-depth conversation what’s special about it for you, and you told me why you chose this quilt for the interview. You have answered quite a lot of my questions without me even asking them. What do you think someone viewing this quilt might conclude about you? Has anybody ever seen it in an exhibition perhaps and given you any observations?

NR: It has been exhibited. At the end of the City and Guilds course we had a students’ exhibition so everybody’s stuff was presented there, and people have always admired it and, but I think it’s not a quilt that people can kind of ‘read’ very easily. I think it’s quite personal in a way and it doesn’t, it needs somebody to interpret it, it’s not one that people can perhaps look at and sort of say “Yes I can see things”. But when I have talked to people about it when I have shown it to them and they kind of said “Oh yes I can see the gardens, I can see the hills”. Somebody commented about this block here which is the night sky, how it does actually look like stars shining in the night sky and there’s meant to be a sunset there so that’s pleasing that people can recognise things. I suppose the comment that sticks in my head because it came from my mother, as she looked at it and she said “Well aren’t you going to embroider over those words?”

JH: [Laughing] Things are never good enough for our mothers, are they really?

NR: [Laughing] No. That was a little bit of a downer, but there you go. And maybe now I would try and do it by machining the words, but I didn’t have the competence on the machine to do that then so using markers was as good as it got.

JH: And when you’ve got neat handwriting, why not?

NR: Well, it’s neatish but there are a few blobs, but anyway there we go. I’m not sure what it would say to other people but in a way it doesn’t really matter because it’s about us and that’s what’s important.

JH: The story of your life to that point.

NR: To that point, yes.

JH: And you’ve told me that you use it on your bed, you use it regularly on your bed, it can change according to the season, it can be useful on its own or as an addition, and it’s obviously well-loved and well worn. Have you any plans for this quilt; you’ve said that it’s getting frayed in places so what plans have you got for its future?

NR: Well we will go on using it. I suppose at some point or other I might do something about the frayed bits. I’m not sure that I would replace them, the ones that are frayed. What I might do is perhaps I might stitch some fine net over them, just to stop it falling apart completely, because in a way the wear is also about a relationship, and about the longevity of a relationship because this year is actually our 40th anniversary, and I think that was also partly why I chose to talk about this on this occasion because it seemed appropriate to share that.

JH: I suppose in terms of a marriage even if it’s sometimes worn, as with this quilt, it’s still well loved, it’s still a well-loved marriage.

NR: Well yes, there is that thing about we do wear, don’t we…

JH: Yes, and yet there is still lots of use left in us…

[NR and JH laughing]

NR: Absolutely!

JH: Brilliant. That’s a really fulsome story about this quilt, which deserves it really because it is such a full and intricate quilt. Such a big story.

NR: I’ve never made one as complex as this since.

JH: You might do for your… you’re not going to start one for your Ruby Wedding then?

NR: Ooooh, I don’t know. No I don’t think so.

JH: Might you start one for your Golden Wedding?

NR: I was going to say, well if I start now for our Golden Wedding!

JH: That was the first quadrant of questions, which concentrates on the quilt which you have used. So now thinking about your involvement in quiltmaking in general. Obviously this is a passion for you and, being in your home, I can see so many things that you have made. Tell me about your interest in quiltmaking.

NR: Right, OK, well, I started making quilts in the early 1980s and I can’t remember now why, but somewhere or other I had seen a cathedral window technique, and I thought “Oh I like the look of that” and I had a friend, a work colleague who was expecting her first baby and so I decided to make her a cot quilt using cathedral window. So I had… Laura Ashley in those days used to sell bags of offcuts. I had a bag of those in lovely, pinks and yellows and blues and pretty floral prints and things like that so that was the centres of the windows and the backing was a sort of creamy yellow polyester sheeting (laughs) because I didn’t actually know where I could get 100% cotton fabric in plain, so that’s what I used. And I made them by hand. I made that one for Sally and for her first baby and she, she loved that. And then I made one for each of my siblings when their first child came along so, and then I had a bit of a break and we moved up here to West Yorkshire. And then for my 40th birthday my husband bought me a course at Gawthorpe Hall in Padiham. They had a residential course for I think it was three days, to learn how to do machine quilting because I’d never used the machine to quilt at that point.

JH: Right.

NR: So I went on this course and it was really quite revolutionary because, you had to have a rotary cutter and a cutting mat and a ruler, and I’d never used these things before and I didn’t know anything about them, and it was a real eye-opener that you could actually cut your fabric so easily and it would all be exactly right, that there wouldn’t be any kinks or jinks as you cut out and that you could machine it together and you could make blocks. So we were shown how to do this block and originally I think the idea was that you would make eight blocks and you’d have a wall hanging. Well I got carried away and decided to make a double bed quilt.

JH: As you do!

NR: As you do! And I still have that quilt and we use that one as well, alternating with this one, and I painstakingly quilted it by hand, not very closely I have to say. Quite far apart [laughing], took me ages, but I was very pleased with that. And then in the early 1990s I saw that the local college they did the City and Guilds and I decided to enrol for that. And partly it was a bit of an antidote to work.

JH: Right.

NR: Because I was working full time as a social worker and it was all quite stressful so having something that was creative, different, was just so helpful. And it was a bit daunting at first because we had to ‘do design’ – and I really didn’t, didn’t have much of an idea about what that might mean and people were talking about these design sheets and things like that, and we would be given this, topic and we were supposed to make a design. But once I kind of got my head around that, that was really quite exciting and I’ve still got all my design work and things.

JH: Right

NR: And I’ve got one or two that I keep thinking “I must go back to that because I think I could make something out of it”. And you had to do a lot of other things as well, you had to explore techniques. We did a lot on fabric colouring so this is where I learned about the dying techniques that I’ve used in the quilt that I’ve been talking about. We looked at fabric manipulation, and how you could use stitch to create different kinds of textures and things like that. Oh, so much over that four years of doing the course. I learned so much just quite amazing when I think about it. And I made some very good friends. People who I still meet every so often, every 6 or 8 weeks and we still sew together and encourage each other and talk about what we are doing and what do we think about this or that and the other. What am I talking about Julie? I’ve lost the thread now!

JH: You are telling me about your interest in quiltmaking which is fascinating.

NR: I’m just going on! Yeah.

JH: So it started from a very simple gift, really and then it’s developed into a real passion, a lasting passion.

NR: Yes I suppose it has and it’s something that’s just part of my life now, it’s what I do. If somebody has a special birthday or a particular event, I make them a quilt or a wall hanging.

JH: So it’s a big part of your life?

NR: I suppose it is. I tend not to think about it in that kind of terms but, yes I think it probably is.

JH: And I guess what age were you when you started making quilts, were you about 40 did you say?

NR: Yes I was in my thirties I think when I started doing the cathedral quilt. I had done a bit of English patchwork over papers, hand stitched, as a teenager, and I can’t remember why I did that. I certainly made a cushion cover using hexagonals and in fact I was doing a bit of tidying up the other day and I actually found some rosettes that I had left over [both laughing], so that’s made with sort of 40 year old fabric, it might even have been older than that because I was using up things out of the scrap bag that would have been quite old by then. And I do remember when I was really quite little, still playing with dolls’ prams, that I decided to make a blanket for the doll’s pram and I remember it was made from a piece of corduroy, a piece of tartan and a piece of pyjama fabric and I kind of chose them because they were sort of rectangles and if you put them together they came to about roughly the right size and shape…

JH: …as the pram [laughing]

NR: and they were stitched together and I think I probably stitched them together, cobbled them together by hand and that was the dolly’s blanket. And I’ve still got a really clear visual kind of image of that and I was probably about, I don’t know, eight or nine when I did that.

JH: And thinking about that paper hexagonal technique there’s no wonder we didn’t stick at it really is there, if we learned that way?

NR: Not really. It takes a long time to get anywhere.

JH: You’d have to be really dedicated to think “This is my life’s work”? [Both laughing]

NR: Which is why the course that I did was just such an eye-opener.

JH: Mmmm. Yes. How things have moved on.

NR: But it made it, for me it made it achievable because it is about actually being able to produce something fairly rapidly and to use the machine and not do it all by hand which is a bit painstaking.

JH: And I’m thinking about what you’d said about the dolly blanket. Did you have people in your family that already quilted or sewed, or was it just coincidental there were three scraps of fabric?

NR: I think it was coincidental. But I mean mum always made our clothes when we were little, and my grandmother sewed and crocheted and knitted. But they didn’t make quilts, although I do remember a blanket that granny had made which was made out of pieces of felted woollen fabric that had been stitched together so in one way that was a bit like a quilt. And mum did sort of knitted squares and sewed them together, and that kind of thing, but nobody quilted as such.

JH: No, not the way we know it nowadays.

NR: Not as we know it nowadays, no.

JH: How many hours a week do you currently quilt?

NR: Right. That does vary a bit because I am still doing a bit of work so on the weeks when I’m working then I might not get very much done. But then I might be able to spend a couple of days perhaps working on something, and if I’ve got something that I need to finish because there’s a bit of a deadline then I’ll put more time into it, I’ll manage it so that I can do that. I’ll do it. I’ve got a quilt at the moment for my great nephew’s first birthday which I’ve done all the piecing but I need to layer it up and quilt it so I’ve got two weeks left to do that so I’ll be doing a few more hours in the next couple of weeks.

JH: They’re going to be busy weeks.

NR: It is quite variable depending on, and at the moment the garden calls because there’s a lot to do.

JH: And you’ve got to be out there getting inspiration for next time.

NR: Well that’s right.

JH: What is your first quilt memory, is it the little dolly blanket that you made do you think?

NR: I think it is actually, yes. Yes. And I don’t know quite what fostered my interest. I mean I’ve always been quite interested in needlework and associated kind of crafts and things like that and there’s just something about patchwork that’s always appealed really.

JH: Maybe it’s the age of us that we are make do and mending.

NR: Well I think that, yes, that has got a strong element for me. It was a bit of an eye opener to me that you could actually buy fabric to make a quilt rather than use up dressmaking scraps or whatever.

JH: And you’ve said that there aren’t quilt makers, it’s not a particular heritage that you’ve gone through with your family but you’ve got friends that you still quilt with from your City and Guilds.

NR: Yes. And you meet people, don’t you, and find out that other people have got a quilting interest so you develop a bit of a network of people who are interested in similar things.

JH: Definitely. And what impact does your quiltmaking have on your family?

NR: Well I think everybody in the family has got one of my quilts, or at least a cushion, and I know they’re cherished, I know nieces and nephews I’ve made them quilts ten, 15 years ago they still use them. When they get married they get a double bed quilt. That’s the wedding present. That’s what I’ve done up to now. I ask them first. I do ask them “Would you like it?” because there’d be nothing worse, would there, than getting something like that and thinking “bleeaaghhh. Not my taste at all.”

JH: And nothing worse for you with the love that would gone into it, and then somebody opening it and saying “Hmmm, not a toaster then?”

NR: It would be awful wouldn’t it? So, yes, those things I know. Some of them like this one are getting a little bit frayed around the edges and I have sort of said, well if you, I know one of my nieces the binding on hers has frayed because I used bias binding for that, which wasn’t a good idea but at the time I didn’t know any better, and it needs a new binding so I’ve said to her “if you let me take it back I will put a new binding on for you.” She hasn’t sent it yet but I will do.

JH: Maybe she can’t bear to part with it. And I’m going to imagine that you do talk about quilting with other people because you’ve said that you make links wherever don’t you?

NR: I do. I just feel that, I find that people who are interested in quilting are very generous in terms of sharing ideas and knowledge and that’s part of the pleasure of it for me. And I do think it’s something that actually kind of binds people together and I enjoy that aspect of it as well. That people from quite different backgrounds and professions and that can have something that they share.

JH: Mmmm. All interesting. And I think you’ve alluded to this already in terms of your work, but I’m asking have you ever used quilts to get you through a difficult time?

NR: Yes I mean [pause: 4 seconds] there was a particularly difficult period of my life I can think about where things were very difficult professionally, and I think quilting was a way of being able to shut all of that angst down and just focus on something that gave me pleasure and that took away the anxieties and the worries. And that was creative at a time when it felt like there was lots of destructive stuff going on that was all quite difficult so yes, I think in that aspect it’s really been quite important in getting through that. And that’s a good few years back now and gone, done with.

JH: Yes. But still it’s a source of comfort and it’s something, I guess, that you could think that it may be the reason that you’ve not had difficult times since then is because you’re quilting, it’s maybe seeing you through without you knowing.

NR: Yes I suppose, yes perhaps it’s a treasure. I’ve kind of set myself other challenges. I’m just thinking about I actually set myself a challenge of doing a PhD which I did part time, it took me eight years and at times it was like “I can’t do this, I cannot possibly do this” and certainly quiltmaking then had to be very kind of, it had to be things that were very achievable but it was important to have that opportunity to do something that I could do when I was struggling with this kind of feeling of “This is just too much, too big.” But yes it kind of helped me get there in the end. And in a way one of the things I found was doing the PhD was a bit like quiltmaking.

JH: Right.

NR: Because its, when you doing a PhD it’s your own project. Nobody else has done it. You’re the only person who has explored this particular question and so you have to create a design for doing it: how are you going to find out the information that you want; and in a way you go through the same business of building the blocks because you have to read and research blocks of information and then the final challenge is putting it all together. So there were actually quite a lot of parallels.

JH: You’re kind of making your design sheets first…

NR: Yes.

JH: Right.

NR: And then that whole bit like when you’ve got a big quilt and you’re sort of thinking “How am I going to manage to quilt this and turn it into something complete?” that’s the same sort of thing when you’re writing your thesis. So I actually found the quiltmaking, having been working on quilts, helpful in giving me a sort of framework to try to tackle this academic challenge.

JH: Yes, something so creative can be influential in an academic subject.

NR: Yes, so that was quite interesting.

JH: And interesting that you’ve been able to see those parallels, that it’s not something that’s completely separate in your life, it’s actually complementary to other things you’ve been doing.

NR: Yes.

JH: Goodness. Have you an amusing experience that’s occurred from your quiltmaking?

NR: Well, there is one. I have this log cabin quilt. It’s a very big quilt and it’s still not, I started it ooooooh I think actually before I completed City and Guilds, so nearly 20 years ago, and it’s still incomplete, it’s still not finished. [Both laugh]

JH: It’s a UFO [unfinished object]

NR: It’s a UFO, yes. And I took this quilt to a, oh what do you call them, you know where you go away, and you stay away…

JH: A retreat?

NR: That’s it, I couldn’t think of the word I want. A quilt retreat that was being run by Lilian Hedley who teaches traditional wholecloth quilting, and I got to hear about this because my friend Penny had been on one of Lilian’s workshops and Lilian had talked about setting up this retreat and they needed a certain number of people to do it. So she said to myself and Rosemary who is also a close friend “Would you like to come?” So we went and I took this quilt to have a go at it because I was struggling with how to quilt it. All the seams and things. Anyway I think our idea was probably that this was also a bit of a holiday. Because you went and this place was lovely and it had big studios and lots of big tables and everything, and you had all your meals provided and…

JH: …always a bonus.

NR: It was all you could do was focus on your sewing. But we also thought that we ought to enjoy ourselves so we went off for a walk one afternoon and I left this quilt behind, and when I came back Lilian and one of the other women had actually tied it for me or had started doing the tying. And so I have this quilt that I can say that “Lilian Hedley tied this for me”.

JH: Oh gosh.

NR: But I must finish it because in a sense then you see Lilian also insisted that I did some hand quilting on it, so I learned how to make a traditional feather, drawing round pennies and drawing it out onto a piece of greaseproof paper and transferring it onto the fabric. So I did all that round the inner border and then there were some plain panels that Lilian suggested I should do square diamonds on, ½ inch square diamonds, sewn by hand and these panels are about, I don’t know, 2½ feet long and 1ft deep, and that’s where I’m stuck because it’s just a lot of straight line sewing and I can’t feel inspired to do it. And just recently I did have the thought that just because Lilian said that’s what I should do, doesn’t necessarily mean that I have to.

JH: No!

NR: I could do something else.

JH: You could!

NR: So I’m just mulling that one over…

JH: …wondering if you dare [both laughing].

NR: Wondering if I dare.

JH: Well, I guess if you’d got a piece of her work on the wall you wouldn’t change it but it’s your work to start with isn’t it?

NR: It is, yes, it is.

JH: Bless. And what aspects of quiltmaking do you not enjoy, it sounds like straight line sewing!

NR: I’m not, I don’t enjoy hand quilting. I don’t mind doing a little bit but it’s not something that I find a pleasure. I suppose the thing that I dislike the most it’s doing the layering up and getting a quilt ready to quilt. And particularly if it’s a bed quilt because it’s just hard work on your knees. And I do it on the floor, I move the furniture, crawl around on hands and knees. I don’t like it.

JH: Not easy.

NR: My knees don’t like it.

JH: They fight back.

NR: They certainly do.

JH: And you’ve mentioned that you meet some friends every six or eight weeks. Is that the only quilt group that you are affiliated to or do you have other art and quilt groups?

NR: I am a member of the Quilters’ Guild, I’ve been a member for quite a while now. I probably joined it when I started doing City and Guilds, so in the 1990s. So I meet my two friends, as I said, every six or eight weeks and then recently I’ve begun to work with another group of people. There’s just five of us who share an interest in quilting and we’re at the stage where we’ve been meeting of an evening and in each other’s houses but we’ve decided that we need to be a little bit more formal than that in the sense that if we are going to do any sewing we need to spend a bit longer and have a focus so that’s the beginning, I suppose, of the sewing, of a quilting group that might or might not survive. I don’t know. It depends on how it works and whether people feel it’s what they want to do. I know there are some quite long-standing quilting groups in Huddersfield but I don’t actually belong to them.

JH: And no other art type groups that you belong to?

NR: No.

JH: So quilting’s your artistic outlet?

NR: It’s my artistic outlet, yes.

JH: What are your favourite techniques and materials for quilting?

NR: Well cotton is great, and the range of fabric that you can get is absolutely amazing, although the outlets for it seem to become more limited. But I do use other fabrics as well, I do use velvets, cotton velvet and silk, just depending on what I’m doing so those kinds of things I might use in a cushion cover or something like that. And I would like to get back into dying my own fabric.

JH: Right.

NR: I’d quite like to experiment with using natural dyes and just sort of see how that works, but that is a retirement, when I am properly retired, project.

JH: So when it won’t impact on your true quilting?

NR: Yes. [Both laughing]

JH: Quilting’s not going to be out of the window for that.

NR: No, no, no, no.

JH: We talked earlier about the difference between when you were younger and you quilted and then when you went to the workshop and they’d got the rotary cutters and such like. So what other advances in technology have made a difference for you for quilting?

NR: I suppose over the last 15 years I’ve upgraded my machine so that I’ve now got a machine that has a range of quilting stitches and a range of embroidery stitches, and it’s got a wider throat so in that sense that technology has been good. I do use a camera quite a lot.

JH: Right.

NR: I take lots of photographs of things that interest me, whether it’s stone walls or corrugated iron barns, or things like that and that’s about colour and texture and things. I don’t necessarily use them directly but they all sort of contribute to my thinking about things. And when I’m laying out a quilt and I’ve got to a point where I’m satisfied with where the blocks are then I usually take a photograph of it and then I print it out and I use, I keep that as a record then to make sure I’ve got blocks where I want them.

JH: Yes.

NR: So I suppose a digital camera is a piece of technology that I find very useful.

JH: Support technology?

NR: And my husband has tried to interest me in using computer-generated design programmes but I haven’t really got into it. I mean I was doing some sorting out the other day and I found all the disks for ‘Quilt-Pro’ which I have never used but he bought me for Christmas one year, so I’m a bit of a dead loss in that area really. But the rotary cutter, amazing piece of technology! A seam ripper!

JH: A ¼ inch ruler!

NR: Oh yes, a ¼ inch ruler yes, that’s a really useful thing. And I do have some square rulers for when you want to square up blocks and things like that but I don’t have, I don’t, I tend to be a little bit sceptical about gadgets and things like that because I think often you see them and you think “Oh yes that looks really good.” But do you actually ever use it? Because I’m very cautious about spending money on those kinds of things. So yes I suppose as I said, the digital camera, my sewing machine and that’s about it really.

JH: Okey dokey. And the space that you work in. You’ve said that you can clear the floor and lay things out ready for quilting but where do you do you normally work, where do you sew?

NR: I do have a room of my own which is at the moment is a bit of a combination of a sewing room and a study and I kind of… I’m in the process of making it more of a sewing room, but it’s a bit of a mess at the moment because there’s too much in it, and it’s in transition, but it’ll get there in the end. And I have this lovely big table that allows me to spread out. And I’m trying to order my fabrics and store them in a sensible order but at the moment there’s too much. I can’t fit it all in.

JH: They’re fighting back!

NR: They’re fighting back! [Both laughing]

JH: The fabric is coming to meet you.

NR: The fabric is coming to meet me! And one of my current challenges to myself is to try and make a dent in the stash and not purchase anything unless it is absolutely essential.

JH: And on the subject of purchasing things…. have you any idea how much you would normally spend on quilting?

NR: I’ve thought about this and this year I think, because I went to the Quilters’ Guild conference so that was about £400 with the accommodation and rail fares and all the rest of it, and then I go to Birmingham so that’s another £100 and I usually go to the Knit and Stitch show in Harrogate which is easily another £100, so that’s £600…

JH: And no quilt to show for it!

NR: And no quilt to show for it! And then there’s magazines and the occasional book and then if I’m doing a special project, like last year for my sister’s 60th I made her a double bed 90” square quilt so that was about £200 for the fabric and the wadding and that, so I suppose it could be up to £1,000 in a year which is kind of a bit of a shock really.

JH: When you think about it?

NR: When you think about it.

JH: Do you have people saying to you “That’s beautiful. You ought to make these to sell.” And you say “Seriously, would you pay £450 for this?” [Both laughing]

NR: Absolutely. And that is the issue isn’t it?

JH: Absolutely.

NR: And I think it’s an issue for quilting generally, because will people pay what it actually…

JH: And if you were to put minimum wage on it…

NR: I was going to say, that doesn’t take any account of your time, things like that.

JH: We’re priceless. My eldest son had said to me at one point “You know mother I’m sure I could make money out of this” and I said “I could make more if I charged for childcare, what do you think?”, and that shut him up!

NR: Yes. I mean because I kind of got to a point where I can’t, how many quilts and cushion covers and things can you give to your family and friends. There is a limit. So I have actually got an online shop on ‘Folksy’.

JH: Right.

NR: I suppose this is a bit of technology that I use actually that I hadn’t thought about.

JH: Yes.

NR: But I have my cushion covers and bags and things, and that’s a kind of new development that’s something that I’ve begun to do now I’ve got a bit more time. And I have had one sale, which was very exciting.

JH: Right. So what we’d need to think about then perhaps is not just “How much are you spending in a year” but also if it’s generating an income for you?

NR: I got £15 pounds for that, an 18” square cushion cover, simple 9-block patch. But, yes, I had made it anyway so rather than it being in a cupboard it’s possibly, hopefully, gone to a good home.

JH: We’ll cross that £15 off the £1,000, it brings it down a little bit! Are you OK if we carry on? We’ve finished two sections now, we’ve two more to go.

NR: Yes sure.

JH: OK. So we are thinking now about the craftsmanship and design in quiltmaking. What do you think makes a great quilt?

NR: Right. I think that can be quite varied. I mean when you go to shows and say you go to Birmingham or to one of the other big quilt shows, there’ll be quilts that I admire because of the technical competence, there’ll be quilts that I admire and am impressed by because they say something to me, and then there will be quilts that just completely blow me away because of the colour or the way the design just speaks to me and it might not be figurative, it might just be that it sort of just presents a kind of rhythm or a mood or an atmosphere. So I think it’s quite difficult to say what makes a great quilt, and because it doesn’t always have to be something that’s perfectly sewn. It could be something that is in some respects imperfect in its execution but, because of the subject or because of emotion that it evokes in you, I think that’s a great quilt. So I don’t think there’s any one thing that I could say makes a great quilt. There’s a whole range of things.

JH: Something that speaks to you.

NR: Yes and it is quite personal I suppose. And I suppose it’s like art isn’t it? You can look at pictures that are there because they are by great masters or whatever but they might not move you because they don’t resonate for you, whereas others do so it is quite personal as I say.

JH: Definitely, and a lot of it is to do with colour and the way that rings a bell somewhere inside you that you think, you’re not sure why it connects but it does.

NR: No, but it does and it might just be about, like you say, with the colour that it might just evokes for you autumn or spring or something that’s special and I mean, occasionally I find I look at some quilts and I’m just overwhelmed by a sense of desolation because of the sadness that comes from them, and there was an exhibition of quilts by somebody, I can’t remember her name, but she’d produced these quilts based on photographs of people from Africa. Now I found those very, very moving and very sad. So it just depends really.

JH: Would that have been a great quilt in its own way do you think?

NR: Yes I think so because it has a power to affect people.

JH: So it’s not just about a joyful sense of it?

NR: No, no. Absolutely, it can be about… I remember seeing years back now, there was a woman who did a whole series of quilts that were based on, she was from Northern Ireland and these quilts, each quilt represented a year and they were significant events that had occurred in the year and most of them were to do with the troubles. And they were very powerful because they said something around this very deeply felt long-standing struggle in which people were dying. And so they said something very powerfully.

JH: It’s a whole passage of history isn’t it?

NR: Yes.

JH: Goodness. And that kind of sums up also what makes a quilt artistically powerful, again it’s evoking something, some response from you almost?

NR: I think so, yes. I mean there are some quiltmakers who produce graphic images, that are a picture, and some of those are quite amazing. But that, I’m not, I don’t kind of engage with the ones that are just almost a perfect replication of an image. I prefer something that’s a little bit more abstract, where you’ve got a bit of I suppose it’s your own personal interpretation comes into it as well.

JH: Yes. So what would make a quilt appropriate for a museum or a special collection in your view?

NR: I think there’s quite a few things that might make something special for a museum or a collection. So one of them might be because it’s unique, it’s an example of a particular technique or approach that doesn’t exist anywhere else. Or it might be because it has history, it’s got age, it’s 300 years old and quilts are fragile, they disintegrate and disappear because they’re used, they wear out. So that’s its value. And I suppose things that perhaps represent a particular time or age. I noticed recently the Guild had acquired a patchwork bikini.

JH: Gosh.

NR: And I thought that is just so evocative of the 1970s because that was the beginning of patchwork coming back and people were experimenting with making garments out of, it’s made out of hexagons.

JH: Yes, being very bohemian.

NR: Yes. I think its things like that. And I was lucky enough to go and see the V and A exhibition and that was like historic continuity through time, but there were some things included in that that I wasn’t quite sure that I thought were particularly good examples. They had a Tracey Emin installation as part of that and I didn’t really think that was a quilt.

JH: No. But maybe the name was sufficient to draw people in?

NR: Well I suppose it was about perhaps people experimenting with different things because it was about layering and things like that. And I mean the other expert, the other aspect of it is being able to have the opportunity to look at past expertise so when you see things like quilted petticoats and waistcoats and nightcaps, the stitching and the detail is just amazing. And that in itself is part of why certain things should be preserved in museums or special collections.

JH: For us to learn from.

NR: For us to learn from, and to admire, and to understand people’s past ways of living and clothing themselves, protecting themselves.

JH: And the stitching that they did with no light,

NR: Without light…

JH: The short hours of daylight they’d got to get that done.

NR: By hand, you know without a sewing machine and that kind of thing, it really gives us pause to think.

JH: Whose works are you drawn to, and why?

NR: I do like some of Pauline Burbige’s work. I particularly liked some of, she did some work a few years back which was actually using lamination, so it wasn’t a traditional quilting technique at all. It was laminating together fabrics, plant material, things like feathers, things like that and then joining them with eyelet rings and that was quite intriguing. And I also liked the work that she did which was quite graphic and that was, there was a fishy sequence. Coffee pots was another one that I remember. And it was really about playing with colour and different sizes of blocks, and moving them. She’s a really experienced, well-known, internationally recognised quilt artist so that’s…. I don’t even aspire to producing work like hers but I can really sort of get excited by the colours and things like that. And I look at bits and think “Oh yes maybe I could use a bit of that and do something like that.” So that’s one, and Deirdre Amsden’s work doing the colour wash, that was quite intriguing. And I can admire somebody like Gwenfai Rees Griffiths (I think that’s her name or is it Griffiths Rees?) who does this most amazing intricate appliqué and quilting, stunning work, it’s absolutely incredible. And she has exhibited at Birmingham and won prizes but I would never work in her style because it’s not one that appeals to me.

JH: So would you say that both of those are great quilters? Is that what makes a great quilter?

NR: Yes but very, very different in terms of what they produce and then you’ve got people like Annette Morgan (I think it’s Annette Morgan, I’m dreadful on names) who are quite, who’s quite abstract, and painterly and modern art kind of thing and I can be inspired by that as well. So I think there’s lots of inspiration from other people who have expertise.

JH: And it sounds to me as though you seek that out. That’s something that you would do, go to exhibitions specifically to learn about these kinds of things.

NR: Well, I go to exhibitions, yes, but I also go to other things. We live quite near the sculpture park and I go to exhibitions at the sculpture park and I see different kinds of things there that also inspire me, and make me thing about colour and shape and texture and stuff like that so I suppose that’s one of the things that City and Guilds actually did give to me. It really makes you open your eyes and notice what’s around you and I think that is a great gift and I’ve really integrated that into my life so I am doing it all the time, kind of thing.

JH: You’ve really absorbed that haven’t you?

NR: Mmmmmm. Yes.

JH: What do you think about machine quilting versus hand quilting? You’ve done lots of both by the sound of things.

NR: I haven’t done a lot of hand quilting. I’ve done bits but I would always choose machine quilting. I wouldn’t say I’m a brilliant quilter. My free-motion quilting is not as good as it should be. I don’t always get the stitch length regular. I occasionally have a big leap. But I keep persevering and I keep thinking “it’ll get better, I’ll keep trying.” And I can appreciate hand quilting and my friend Penny does hand quilt and she thinks nothing of hand quilting a wholecloth double bed quilt.

JH: Oh, my days!

NR: She will do that and she finds it very relaxing. I don’t! I find it quite stressful. I can do a cushion cover and that’s about it. I think they have different, they are different kinds of things. I think hand quilting is something you can actually do perhaps while you are sitting with the TV on, or in the evening. It can be companiable, whereas machine quilting it’s not companiable because the noise of the machine and all that sort of thing.

JH: A bit more solitary.

NR: A bit more solitary, yes.

JH: And what about long-arm quilting?

NR: Yes. I have had one of my quilts long-arm quilted. It was for my nephew’s wedding. It was a big quilt and at the time I didn’t feel that I had either the time or the space to manage it myself so I decided to have it long-arm quilted. And there is something about having an all over design that’s been well executed that sort of makes things look very good and very finished. But there is that bit about it’s not all yours then. And I was a little bit disappointed because although I had given the quilt to the person who was going to do it four months before I needed it, for a variety of reasons she didn’t actually do it until two weeks before the deadline…

JH: Gosh.

NR: …and I had, I had made a very silly mistake in that I hadn’t, when I put the outside borders on, I hadn’t measured them properly so there was a bit of slack in them and when the quilt came back there were actually pleats in it where the fabric had folded over under the machine, and I was a bit disappointed about that. And I did feel that, given the amount of money that I paid for it, it was not quite what I expected, and that if she had started it earlier, it might have been possible to rectify it because she could have said to me “Look Nicky…

JH: “This is what’s happened”

NR: … your borders are too slack, you need to take them off and reapply them. It’ll be better.” But anyway so I haven’t had another one done since then. But I do, I have looked at them at shows when they have them and they are huge and very expensive as well so it’s not something that a) I can afford or b) find space for. And as you were saying earlier I think it would be good if there were a facility perhaps to be able to go along somewhere and rent time on it, but maybe that will come because there will be a demand for it I suppose.

JH: I wouldn’t be surprised at all. So last section on the interview. The function and meaning of quilts. Why is quiltmaking important to your life?

NR: [5 second pause] I suppose because it is an outlet for creativity. There is something about the satisfaction of producing something that’s functional and it’s something that enfolds people, that they sleep under, or they wrap around themselves, and that feels important to me, that there should be that element to it. And I think the other thing is the tactile aspect of quilts, you know? You want to touch them and be able to scrunch them up or whatever so there’s that that’s important. And I think they do give pleasure to people. So a lot of my quilts are gifts to friends, to family, and that’s pleasing. I like being able to do that. And then in a sense those quilts that I’ve given become associated with that person so upstairs I’ve got one that I made for dad for his 80th birthday and then when he died I asked mum if I could have it back, so every day I see that quilt because it’s on the table upstairs on the landing. It just, it just, you know, speaks to me of dad at that particular time.

JH: That’s nice.

NR: Yes, it is nice. And, yes so I suppose that’s what quilts mean.

JH: Do you that think that your quilts reflect your region or community. Or because I’m aware that you have lived in several different places obviously your first one reflects that, it depicts that in a way, but in terms of what you do now does that reflect the community that you live in or the region that you live in?

NR: I wouldn’t say directly because my current quilts are probably much more about colour and using simple blocks and colour combinations and that sort of thing, but I am aware, partly again because of City and Guilds, that there is a history of quilting in Yorkshire and that there is actually in the Guild collection a quilt that was made at Mirfield in the 1800s, and I’m very conscious that I actually live in a village that had a very strong weaving heritage, hand loom and on machines. So I’m kind of conscious of that and I do think that partly the countryside and that also contributes to part of my thinking around quilts and things like that. And certainly when I made this quilt it was really important to me that there was something in it that represented the coal mining because that was a really significant part of living in the Welsh valleys, you know, and mining is also significant here. So in that kind of sense I suppose there’s some part of it but it’s not direct, it’s not a particular regional style or anything like that.

JH: No. What about the importance of quilts in British life?

NR: I think this an interesting one, and it refers back to that one about can you earn money from your quilts, and historically there were women who earned their living from their quilting and it was quite a recognised thing that perhaps if somebody was widowed they might then create a quilt club and so many people would contribute so much and then they would make a quilt, buy the materials and make a quilt and give it to that person, then the next person would get their turn and they would do it like that, and that was really hard work, a hard way of making a living. So I think there’s something around about quilts that’s been part of our history, there’s also that whole kind of thing about ‘make do and mend’, about making something from things that are used up or would be otherwise disposed of. That certainly appeals to me. But I do think that currently I can’t, I suppose I can’t see us ever getting back to a position where any but a very few people, like people who are really recognised as quilt artists like, for example, Pauline Burbidge, could earn enough from quiltmaking. And there are people who do manage to make a living from some of their quiltmaking and from teaching about it and writing about it, which is quite hard but it’s quite a small group of people. So I’m not quite sure what, how quilting fits into contemporary life. I think there’s a lot of interest. I think there’s a passion for it. I think there are a lot of people like ourselves who make quilts and who love them and spread that to their families and their friends. But whether it would ever become something that was recognised as something of significance in British life or not I think is a bit doubtful.

JH: You’ve mentioned about quilts having special meaning for women’s history in Britain. Is there anything else you wanted to say about that? You were saying about women if they were widowed could earn money from making quilts. Is there anything else about women’s issues do you think?

NR: I suppose in a way there’s a whole kind of thing isn’t there, that there’s a kind of parallel between the significance of women as ‘the makers of the home’ and of having the skills and the knowledge to keep their family healthy and well fed and well clothed and that, and I think quiltmaking is part of that because it’s part of that thing about making bed covers and keeping your family warm. And I think that’s really quite important and significant. And I think there’s currently a growing interest in the skills associated with producing things like that and younger people are beginning to rediscover those, but quite where it will go off to I don’t know.

JH: And previously, in history, there’s been a point where if a shirt collar was worn out, the rest of the shirt had to be used, whereas now we’ve so many outlets where you would put something for recycling so the tendency is, “Look put that to recycling, start again with fresh material”. Recycling has a different element, we don’t have to use that material twice. There’s no urgency to making a quilt out of, it’s almost just an ironic thing that you would use a piece of material twice nowadays isn’t it, rather than necessity.

NR: Yes.

JH: So, how do you think quilts can be used and similarly preserved for the future? Two sides of the same question.

NR: I do think there’s a very practical usage for quilts which is as bed coverings, to adorn the home, to give people pleasure, things like that and I think that’s really, really important and probably just as important as having some overall place where quilts are preserved as a sort of historic record or as an artistic statement and I think the two things are really closely entwined. And the one that kind of drives you probably depends on your position in a sense, I mean I would be very pragmatic in the sense that I see quilts as something that should be useful rather than as pieces of art. Although I can admire the art and enjoy it but that wouldn’t be the quilt I would make, generally speaking.

JH: And maybe again, technology is going to make it more easy to preserve things than it had been in the past because of the different fabrics and the threads we use.

NR: Yes and I suppose we understand more about how damaging things like sunlight and air and that sort of thing can be. But I think it’s probably always going to be a bit of challenge, isn’t it, particularly if things have been used, well used over a period of time then they are not going to be pristine are they?

JH: That’s part of the fabric of them almost. You’ve mentioned a few times about how the quilts that you’ve made for friends and family how they have been used and well loved, and almost need re-doing again because they are so well loved. What do you think is the biggest challenge confronting quiltmakers today?

NR: [6 second pause] I think there is a possible danger that it can be over-commercialised, that it can all be about kit and gadgets and techniques, and so I see that as detrimental to the real essence of what quilts are about, which is trying to create something… can’t find the word… from lowly things, from a piece of fabric.

JH: Upcycling something?

NR: Yes, so I think that’s a bit of a challenge. I think there’s a lot of interest in handmade things and I think that we shouldn’t be too precious about the way that people make their quilts. If it’s pleasing and it’s functional then it’s a quilt. I think there’s some quite exciting experimental stuff that’s done. At one exhibition I can remember I’ve seen a quilt made out of pieces of old metal cans that have been flattened and sandwiched together but that’s an art piece. It’s not a quilt.

JH: No.

NR: Because I do think there’s something around a quilt that’s malleable and soft and warm and cosy.

JH: Metal wouldn’t do that would it?

NR: Am I answering the question?

JH: What’s the biggest challenge confronting quiltmakers today? I suppose, I think what you were saying was to keep a distance between the pieces that are art and…

NR: Well I think they have different functions and different roles. I suppose as a quiltmaker one of the biggest challenges is the cost of things, because fabric is constantly getting more expensive, and that potential commercialisation. I think those are probably the biggest challenges.

JH: We have covered all the questions that I have been given but I wondered if there was anything else at all that you would like to add that we haven’t covered while we have been talking.

NR: I’ve said so much I can’t remember what I’ve said. But quilting is very much an integral part of my life that I can’t imagine not having it as part of my life. And I’m looking forward over the next few years to perhaps being able to develop a bit more in my quiltmaking and maybe explore some things that I haven’t done up to now.

JH: Brilliant, Thank you very much for your time Nicky.