[souncloud]https://soundcloud.com/talkingquilts/sheena-norquay-and-her-seapinks-at-sandwich-quilt[/soundcloud]

ID Number: TQ.2015.011

Name of interviewee: Sheena Norquay

Name of interviewer: Jane Rae

Name of transcriber: Helen Walland

Location: Sheena’s House

Address: Inverness, Inverness-shire

Date: 30 March 2015

Length of interview: 1:04:52

Summary

Sheena’s quilt brings back memories of childhood trips to Sandwick Beach in Orkney with her mother and sister. She talks about her inspiration for the quilt, how she made it and the inclusion of Orkney words in her design. Sheena talks in detail about childhood influences to her sewing, her introduction to quilting in the 1980s and the developments that have taken place since, including her first experiences with a quilting frame and quilting hoop. She also discusses her changing views on sewing machines and the early days of The Quilters’ Guild in Scotland.

Interview

Jane Rae [JR]: Thank you Sheena for agreeing to take part in Talking Quilts. The quilt you’ve chosen is called ‘Sea Pinks at Sandwick’ and I’d like to start the interview by asking you what made you choose this quilt?

Sheena Norquay [SN]: I chose this quilt because it’s one of the more recent ones I’ve made and it was one that has a lot of personal memories for me. In particular it reminds me of the times that my late mother and my sister used to go to this particular beach whenever we could in the summertime, when I was home on holiday in Orkney. It was quite nice to go there to escape from the farm chores, so my mother always used to sit doing her knitting while my sister and I went beach-combing.

You can see in the distance there’s an island, that’s called the Island of Swona. When I was a little girl there used to be a brother and a sister who lived there. His name was Arthur of Swona and he used to come ashore at Barsick Head every Sunday and leave his wellie boots in an old hut and change for church into his best shoes and after church he used to come and visit my dad and my granddad and he used to tell us stories and I always remember he was a bit like Father Christmas. He had really red cheeks bright piercing eyes and a white beard and he kind of looked like Father Christmas. But sadly he died many years ago and now one of his relatives keeps cattle on this island. The cattle are of great scientific interest now because they’ve been left there many years and they’ve been interbreeding. In fact Adam Hinson from Countryfile was there not so long ago. So that kind of reminds me of childhood.

You can see in the distance there’s an oil tanker on the horizon and since the 1970’s of course the Pentland Firth has seen a lot of them coming in to Scarpa Flow to the island of Flotta to load up with oil which is piped ashore from the North Sea.

The other thing about this quilt is that it shows my love of birds especially Oyster Catchers. So there’s two Oyster Catchers in this quilt and one of the Oyster Catchers serves as a focal point I think and he’s turned his beak towards the other one who’s foraging among the sea weed. The other two birds are Curlews. These were ones that were left over from another project I did for a woman just across the Firth here in Inverness, so I included them in this quilt because I thought it could do with a few more birds.

The other thing is I had wanted to use a picture of Sea Pinks which I had taken quite a number of years ago because it had this lovely curve in it. So I incorporated this curve into the picture here. The reason too that I made this quilt was I’d had this quilt in mind for quite a long time a) because of this photograph and b) because I wanted to do a scene of Sandwick Beach to remind me of the times I spent there with my mother. The reason I started to make it was that a group of us in Inverness took part in Chinese Whispers for the Loch Lomond Quilt Show. The quilt that Gilly Thomson showed me had water on it and it reminded me of the Riviera in France and it had flowers on it and I thought ‘well maybe that’s somewhere she went on holiday, where would I like to go on holiday? And how could I link the theme?’ And so because she had flowers and I thought right I can use the Sea Pinks and use Sandwick Beach which is where I really like to go on holiday because it’s nice and relaxing.

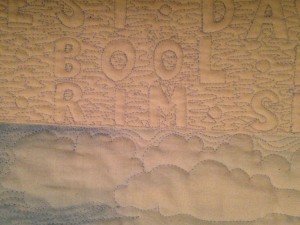

The other thing that I have got in this quilt is that I have recently started doing is old Orkney words, you can see in the top border I’ve got lots of Orkney words to do with the sea and seaweed, and boulders and stones. They’re all free motion quilted in place. And the other thing I’ve done is I’ve extended the actual rocks and grass into the borders through quilting, so only with lines as opposed to fabric like in the main body of the quilt. The birds and the flowers are made by free motion embroidery. The flowers are done with water soluble fabric but the birds are stitched in cotton organdie which is quite good because you know you don’t have to stitch a frame work before you start the main stitching. I’ve also used the cotton organdie for the breaking waves so a lot of the free motion embroidery is done on organdie stretched tight on an embroidery ring first. And then I lay it on top of the pieced background and stitch it on and then quilt it a bit more.

JR: Can you tell me what size the quilt is Sheena?

SN: The size of this quilt is 100 centimetres wide and 75 centimetres deep and it took me about 120 hours to make between the 1st of December and the 18th of January 2014. So I only had six weeks to make this quilt. Normally if I’m doing seascapes or landscapes it takes me a good while longer because I have other projects on the go at the same time. I generally never just work on just one quilt so this is quite a challenge to do it all of a oner.

JR: Do you have commercially bought fabric in there or is it fabric you’ve dyed? Can you tell us a bit more about the fabric?

SN: Most of the fabrics in there are commercial fabrics I’ve got some Bali Batiks for the grass area and all of the stones are all commercial fabrics and the stones are all hand appliquéd. Most of them are Bali Batiks, I like Bali Batiks for hand appliqué because they don’t fray and you get a nice gradation of colour so you can use that for shading, some of the pebbles I’ve made look more 3D by painting the bottoms of them you know just to darken them slightly. And also Bali Batik is good for fusing because some of the seaweed in the distance is fused onto the background with Bondaweb and then to blend the edges I’ve used brown fabric paint to represent what we call tangles and ware.

JR: I know you love free machining and you have done a lot of that in this quilt. Is that probably where you spent a lot of the time in the actual creation of it?

SN: Yes. Yes the free machining does take quite a long time but the planning takes a while as well. And drawing out all these letters took some time and they were quite difficult to free machine because I was going around the outlines of the letters so you only had the one line and it had to be pretty steady when I was stitching it.

JR: I know that you love to be inspired by nature. Does that come from living in Orkney?

SN: Definitely. I strongly believe that your surroundings especially your childhood surroundings influences your choice of what you do, also your colour palette – my colour palette is blue green, kind of yellow, I very rarely use reds and purples and that’s because you were born and brought up on an island. And again the patterns you know on the sand for instance made by the water, I tried to incorporate into this as well. Because whenever I go to the beach my head is bent down looking you know at the patterns in the sand or the colours of the stones and whatever. My mother always used to get on to me for walking with my head down but what she didn’t realise was that I was observing things.

JR: Did you do a lot of drawing and sketching when you were a little girl?

SN: Yes I used to like drawing quite a bit and that went on to sixth year at school. I used to like drawing with black ink, I like doing line drawings. I didn’t really enjoy painting at school because the paint boxes we had were pretty awful you know all the paints were worn away and with holes and all the paint seemed to have run, you know, where it shouldn’t run and it was not an enjoyable experience for me. I quite like using oil pastels I have to say but not paint, although I do use a bit of paint now in quilts now but not for any major part of it only for little details like the island in the distance and the tanker coming in.

JR: Can you tell us a little bit about growing up in Orkney and when you started to sew?

SN: Yes both my grandmothers were needlewomen. My father’s mother she did Fair Isle knitting. She didn’t have a lot of time because she was a farmer’s wife. My mother’s mother was a war widow, her husband was gassed with mustard gas in the trenches, so she was made a widow when her four daughters were less than ten I think, so she had to make do and mend. I always used to stay with her at weekends when I was a little girl, and although she didn’t actually teach me directly, but I think I got a love of fabric from her. She was always making things, she did a lot of embroidery even for WRI’s and won lots of prizes and she did watercolour painting as well. She was really quite accomplished. I think she was born too soon, that was the problem. So although she didn’t really teach me directly, as I say I think I was influenced by her.

And my mother also did a lot of knitting and crochet and she made rugs and made all our clothes. So I reckon when I was about eight I would make dolls clothes and have fashion shows for my dolls. I think if I’d been in the right place at the right time I would have liked to have gone into that line of work as a fashion designer, as all teenage girls used to dream of doing. She taught me how to do dressmaking so when I started sewing I started dressmaking rather than quilting. I didn’t do much embroidery I don’t think, at school except for the cross-stitch on lap bags which I didn’t enjoy, it was too formal. I preferred to do my own thing at home making my dolls clothes.

When I went to college I was lucky enough to do a subject called Two Dimensional Design. And I was taught but the best friend of the famous Kathleen Whyte of the Glasgow School of Art. Her name was May Miller and although we were terrified of her she did teach us how to see the world with new eyes. So it was then that I was taught the language of design, you know shape, line, colour, texture and all that. I always remember she gave us all these exercises to do and we had to explain why we put a line here and why we put a shape there and why did we use that colour. And initially I found it very difficult but eventually the penny began to drop.

JR: How old were you?

SN: Eighteen and nineteen so I had her for two years and we had to make 20 embroideries in two years which was a lot of work in fact there’s one downstairs that I can show you later on. So it was when I was at college one of the girls on the course with me was making a hexagon bedspread and that is how I was introduced to the idea of bedspreads or quilts. We did have one lesson as to how to do patchwork. The exercise was you had a square and you had to divide it up with two lines so you had four shapes. Pick a piece of patterned fabric for the largest shape and then pick out colours in that for the other three shapes and then we had to herringbone the fabric onto card. I did one piece for my final show, and it was a stone spiral staircase, it’s hanging up in the hallway here. So that’s the only piece of patchwork I did for my degree show all the rest was embroidery, hand embroidery, not much machine embroidery because I was terrified of sewing machines at that point.

Although I had done dressmaking that was with my granny’s old hand turning machine. When were at secondary school we were introduced to electric machines because we had to do yet another cooking apron. And I was terrified, it just seemed to run away with me. It was a long time before I actually did any work by machine because throughout the 70s it was all hand piecing over papers and I didn’t see a real quilt until 1980 in Inverness when they had an exhibition of old American quilts. And beside that they had an exhibition by an American artist called Linda Shaker and her quilts would now be called Modern quilts because she used plain fabrics, they were very simple and stitched with thick cotton Perle thread. Whereas the old American quilts to me were very flat and they obviously had cotton batting inside them whereas she had used something which I didn’t know about then, but I discovered was 2oz polyester wadding. So having discovered this polyester wadding I then set to and thought I’d better start quilting.

My first experience of trying to quilt was, I thought the stitches weren’t supposed to show so I actually stitched in between the seam-lines, that was how I started quilting. I bought my first machine roundabout 1980 and I actually started making quilted garments because they were in fashion then. So I made over 72 garments in two years and I supplied a local shop. So the first one had patchwork motifs on the inside and the outside. I had to get them matching up and there was no such thing as a walking foot or a darning foot in those days, so your efforts at machine quilting weren’t very good. But what I discovered was that I didn’t want to have any ends to sew in so on a garment I would start at the top and work my way to the bottom round the motifs. Basically that’s how I quilted. And on the jackets I made which were landscape jackets I started off with a piece of wadding then I started with the sky, quilted that on to the wadding, the reason I didn’t put backing on was that it made it too stiff and it adding on too many inches to the person wearing it. It remained quite flexible if you just quilted on the wadding and then you put the lining in the jacket. But after I had done the sky I started adding mountains and turned under the raw edges and top stitched, as I went, from top to bottom and then added on details like trees and pockets and things, that’s how it all started.

JR: Did you devise these techniques yourself? [SN: I did, yes] And did that take a long time on the machine trying out and practising?

SN: No not really I just went for it. Some of the early efforts when I look back leave a lot to be desired, but the important thing is I enjoyed doing it and you learn as you go and you get better with experience.

JR: When you were in Orkney you didn’t see patchwork quilts there? And it wasn’t something that your mum or your aunts or people in the family…?

SN: No it was in the 1980’s I think when I was at an auction in Orkney and there was an old quilt was there and I bought it. I was lovingly scraps stitched together and it was machine stitched on an old treadle machine. And then my dad told me that when he was a young lad he used to sleep with his granny in, you know, one of those box beds, and he said they slept under twilts T-W-I-L-T-S and that was the Orkney name for quilts.

JR: And can you describe – were they a whole cloth quilt?

SN: No they were scraps of shirts and maybe curtain fabrics I have two of them at home in the Orkneys, there weren’t any patterns to them or anything it was literally stitching scraps together to make something warm to sleep under.

JR: So very functional.

SN: Very functional because at that time they used to have mattresses made out of chaff.

JR: What’s chaff?

NR: Well when they used to thresh oats the machine separated the seed from the covering. The covering of the seed was called chaff and that was used to stuff mattresses.

JR: So you have taken quilting to a whole new dimension compared to the quilts your dad talked about?

SN: Yes.

JR: You are coming at it from a design point of view. So when did you switch from doing the garments to thinking ‘I’d like to piece a quilt top’?

SN: I think it was after the two years of making garments I then learned how to machine piece because a quilter called Dorothy Osler brought out a book on machine patchwork and this was a complete revelation, and I also discovered a book called ‘The Perfect Patchwork Primer’ by Jeff and Beth Gutcheon from America and that introduced me to American blocks. I became fascinated by all the different patterns you could make by putting all these blocks together. So then I started to do machine patchwork mostly traditional block patchwork and log cabin was another technique I used.

So from about 1980 to about ’85 I would say, I did a lot of machine patchwork. In fact, it was up to 1990, no 1989 all that I did was very traditional block patchwork. And in 1982 I learned how to hand quilt correctly because before that, as I mentioned I thought that the stitches weren’t supposed to show. Then after Dorothy Osler was here doing a workshop there was actually a man at the same building as she was doing the workshop, who had an exhibition of weaving looms. She told us about these frames that women used to have you know these great big long nine foot frames for quilting on. So by the end of the afternoon three of us had decided that we wanted this man James Lockie from Dumfries to make us quilting frames and Dorothy Osler drew out the plans. So about six months later this student arrived at my one bedroom flat, which at the time was above a shop, and she was in a Volkswagen Dormobile and she was studying Pine Martins in the Highlands, so he told her to take these three long nine foot frames up to Inverness. I had a problem getting them up the stairs and turn at the top, I had to ask my neighbour to open her door. I remember the first time we used one of these frames was in my friend’s garden in the summertime. And we though that you had to have at least three layers of this polyester wadding to make this quilt, to make it nice and thick, but when we started quilting we could get the needle down but we couldn’t get it back up. And I had read in a book that children used to sit under the frame and push the needle back up, so we took turn about sitting under the frame and poking the needle back up. So because of that first experience none of us really liked the idea of quilting on a frame. So then in 1982 this American lady called Mildred Patterson came across looking for her family roots. She had got in touch with the Guild to see if there were any quilters in Inverness so they gave her my name. She came with her brother and sister to the same flat and it was like Christmas because they brought books and fabrics, and old fabrics as well, and old blocks and this thing called a quilting hoop which I’d never seen before. So she showed me how to use the quilting hook. Because I was in this one bedroom flat and I didn’t want to use a large frame I had this clothes horse which was maybe 36 inches square and I had sawed off the two middle rungs to give me a smaller frame. I thought that would be easier to hand quilt so I did a few pieces on that but this quilting hoop seemed a whole lot easier. You remember Bob Geldof Live Aid Concert, I can’t remember what year that was 1985? [JR: 85 I think that was] In 1984 I had been to America to see Mildred and while I was there I was also given a rotary cutter and cutting board which I had never seen so I took that back. So then I started using that to do strip piecing. Anyway it was when Bob’s concert was on I started to quilt a sampler quilt that I made after being in America and you know buying fabrics from there. So it was thanks to Mildred and thanks to her inviting me to go to America that I learned to quilt properly in a hoop. So I did three or four quilts hand quilted in a hoop, but by 1983 my machine had conked out.

JR: What machine did you have?

SN: Well the first machine I had was a Newhome and cost £99.99. It only lasted just over two years after making all these jackets and waistcoats, it conked out. So I bought my very first Bernina from Bogod sewing machine company in London I think it was. Then in 1984 or 1985 or 1986, I can’t remember, I bought this book by Harriet Hargrave on free motion quilting. At that time I managed to get myself a darning foot and because I had done a bit of free machine embroidery I found it quite easy to transfer from doing that to quilting. And because I had done free machine embroidery in a ring I thought you had to use a hoop for doing free motion quilting so I’ve always done my free motion quilting in a ten inch hoop. So I then started to quilt in this ten inch hoop, free motion. My first one that I did, I remember, was a green satin acetate and I called it ‘Radiation’ and I did part of it with a walking foot and part of it with a darning foot. And she, in her book, had shown me how to do this thing called vermicelli, you know the meandering line, and I started to do that and got quickly bored so I started to push the work backwards and forward to make a jagged line instead. So after that I thought I must explore how I can free motion quilt backgrounds in other ways besides this vermicelli. So I have been doing that since then.

JR: So were there many people doing free motion quilting at that time?

SN: No because I remember The Quilters’ Guild had an exhibition in Aberdeen, in 1990 it must have been, because the challenge they had, was they issued fabric based on Gustav Klimt and we had to make something using this. I had done a piece and I had free motion quilted it with metallic thread in tiny, tiny little circles and spirals and satin stitch and things, and in the whole exhibition there were only three pieces that had been free motion quilted, all the rest were hand quilted, whereas now you are hard pushed to find any that are hand quilted.

JR: And how was that as a quilter, did you find people were open minded about it? Was there any resistance to seeing this?

SN: I think that by 1990 it was becoming more acceptable in America because Caryl Bryer Fallert had won one of the shows with a machine quilted piece and I think that was the first machine quilted piece that was kind of accepted, so it was just beginning to be accepted but not many people knew how to do it, so I started teaching classes, you know, as early as that, on free motion quilting. But a lot of the early machines weren’t very good at doing it because some of them didn’t drop their feed dogs and you had to put a plate on top, I think that if you don’t get a good experience the first time you try it, it can be a bit off-putting.

JR: And what sort of threads were you using in those days?

SN: At that time I was using Madeira cotton Tanne no 50. I did try Sylko cotton 40 initially but the machine just didn’t like that so I found this Tanne 50 at er… sorry I’ve forgotten where I got all the threads – Barnyarns that’s it. [JR: Still on the go] Yes they are stillon the go. But you see they stopped the Madeira Tanne 50 several years ago so I started using Aurifil and then in 2010 I had an exhibition in Birmingham and they asked me to promote their threads and they gave me some free samples and they’ve been giving me threads ever since, in return for making some samples and promoting their threads. The reason I like Aurifil is that, well the number 50 that I use is a very fine thread and the detailed quilting that I do really necessitates using a very fine thread. If you were doing quilting with a walking foot, functional quilting, you would use a slightly thicker one like a 40. Or the Aurifil 28 is a nice one as well, you know you get a very bold line, but they’re just too thick to do this kind of quilting that is on this particular quilt.

JR: I know that in your studio you have almost an entire wall with your threads, threads are very important, would you say it is almost like paint for you?

SN: Yes it is, because you see initially in quilting you were supposed to use a matching thread, the same colour as your background fabric and traditional quilting had motifs on it you know and there’d be some cross hatching, you know, for the hand quilting and even with early free motion quilting you tended to use the same colour thread all over but I’ve always liked to use coloured threads because the colour of the thread can change the colour of the fabric underneath. I discovered that in 1990 when I did that Klimt quilt because I had a rust fabric in one area and a purple fabric in another and I wanted to blend the two together. So I free motion quilted purple thread on the rust and you’d actually think it was a transparent layer of pale purple on top of the rust so there’s all sorts of things you can do with the coloured thread. There’s so much more you can do with free motion quilting rather than hand quilting and of course it’s so much quicker.

JR: I’m restarting the interview with Sheena Norquay. It’s the 30th March and its TD[Q].2015.011 Sheena one of the things I always remembered about you is that you were one of the early members of The Quilters’ Guild. So can you tell me a bit about when you joined and your involvement with The Guild over the years?

SN: I joined, I think it must have been 1980 or maybe 1981 because I saw an ad in a magazine for the Guild so I thought ‘oh I’ll join’. I was sent a letter by a lady called Sue Simper I still have all these letters and she asked me would I be a rep for the Highland Area so I said ‘well okay’, I didn’t really know what it would involve. Then it took to about 1984 before we set up the Scottish committee, I’ve got all the records of that as well, letters from the late Katherine Hogg and Jean Roberts who followed her. So I was rep for this area for about ten years and in fact I was really quite bold because in 1981 I decided we had to have an exhibition. I had been running a house group at that time and I wouldn’t let people join unless they became members of The Guild, so the group was made up of members of The Guild I also had a list of Guild members in the Highlands so we had this exhibition in Inverness in 1980, ‘81 and it was so successful that the curator asked, could we have one every second year. So we had one every second year until I gave up and handed over the reins to my good friend Nan Palmer who’s now in a care home and she ran it for several years and it has gone on and on since then.

JR: Can you remember what your membership number is?

SN: 208

JR: And have you been a guild member ever since then?

SN: Yes I’m actually an honourary member now which is rather nice.

JR: And are you a member of any specialist groups within the Guild?

SN: The contemporary group.

JR: So that’s interesting because I was going to ask you how you describe yourself. Are you a contemporary quilter, an art quilter, a traditional quilter?

SN: I’m really a bit of a mixture of everything I don’t, you know how you’ve got two sides to your brain; the creative side and the mathematical side. Pattern and symmetry appeals to me. I spend a lot of time creating lots of patterns, I enjoy that and it’s very suitable for free motion quilting, but on the other hand I like to sit and create in a more intuitive way. I like to be inspired by stories or, you know, nature, and so I come to it in a completely different way. I try to merge the two together you know in some quilts but in other quilts it’s either one or the other, but I’ve never felt confident enough to describe myself as a quilt artist. I would call myself a quilter. To me the word artist is more to do with painting, I’ve always thought, whereas quilter can cover a lot of different things really.

JR: I think you mentioned to me in an earlier conversation, that you did City and Guilds in embroidery and that when you did that you had a bit of a change to how you approached your quilting?

SN: Yes. Round about the late 1980’s I wouldn’t say I was getting bored with quilting but the urge to find out how to do traditional white work and cut work became stronger. I needed a change and so I discovered that there was a place in London called Stitch Design that offered this correspondence course. Because I was teaching full-time and I couldn’t go to any college, so I had to do it by correspondence and that was really hard. So unfortunately the first block was quilting which, you know, I wanted to get away from that, but the theme was the Egyptians which made me look at other cultures and patterns from other cultures and that was interesting. Eventually I did get on to the cutwork and the whitework. There was quite a lot of drawing, you know, in this but what I found difficult was sometimes they would give you a theme like ‘flowers’ and tell you that you had to do cutwork, well never having done the technique you didn’t know how to do the drawing to suit the technique, because you couldn’t have the holes between the shapes too wide you know and all sorts of complications.

Then when I finished part one, for which I got a distinction, I started part two and it was different because it involved a whole lot more drawing and I remember the first module was medieval and you had to do goldwork which I had never done before. I visited the Burrell Collection and then I studied Elizabethan sleeves, so that kind of got me interested in garments again. And I made a sleeve, you know as one of my finished pieces. But during this time my little one bedroom flat got a bit small so I moved. So I moved house in 1992 and I never got back to finishing Part two City and Guilds Embroidery. So I’ve still got all these sketch books with lots of ideas but it did make me change direction, in that I started to design my own quilts rather than rely on traditional block patterns. So that’s when the story quilts started. In 1994 I started doing a piece called the Three Norns. I had taken the colours from some of the exercises I did in City and Guilds. I made a medallion quilt which I had never done before, but it wasn’t a traditional medallion quilt and many people have said to me that that quilt changed their outlook of how they approached patchwork and quilting. It won me best of show and it won me a sewing machine at the Great British Quilt Festival in 1995.

And the year after that I did another kind of story quilt, what was it called again ‘Vincent and I’ and then I did one called ‘Freya’ and then I did one called ‘The Great Quilt’. Now all these quilts were pretty big, double bed size, and they took about a whole year. I divided them up into small manageable units so I could fit them in with teaching full-time and with planning and stitching at weekends. But after that I got put off doing large pieces because the last one I did ‘The Great Quilt’ took me over 500 hours and it was done for a show at the Shipley Art Gallery. I decided after that why spend a lot of time on one piece. I had so many ideas I didn’t have time to concentrate on just one thing I wanted to try lots of things so I kind of went from making larger wall pieces to smaller wall hangings.

JR: I know that in the notes you sent me you mentioned mythology and the Vikings and myths giving you inspiration, you talked about medieval quilting and Elizabethan thread design, and I know in your studio you let me have a look at you have lots of files, do you do lots of research before you design a quilt?

SN: Well I did for the large quilts, yes I did quite a lot of reading and a lot of looking in books at pictures of designs and things, mostly symbols, I became interested in symbolism after I did ‘The Three Norns’ and I bought a book on symbolism by J S Cooper. So whenever I work to a theme now I have a wee flick through this book and a lot of this symbolism I find quite interesting and that leads me off into other avenues you know, other ideas and including other things in the quilt.

JR Do you make a lot of notes and sketches and planning notes before you sit down to start a quilt?

SN: Yes I do. Sometimes the notes have been going on for years. I have a notebook at the side of my bed because I get most of my good ideas first thing in the morning, you know, or the last thing at night and so it’s not really drawings as such it’s more annotated sketches you know mostly written words with a few sketches just for the ideas. Very often I find myself going back to the same theme but bringing it on you know, a little bit further. But with the mythology ones, yes that does involve quite a lot of reading you know you want to get your facts right. Like in this quilt with all the lettering I used the book ‘Old Orkney Words’ by no, sorry the ‘Orkney Wordbook’ by Gregor Lamb and I went through every single page, it’s a bit like a dictionary, I went through all the pages and take notes of all the words that were to do with you know the border of the beach and the tides and everything you know. There’s one or two for instance, the old Orkney word for horizon is Kulkie, a wave breaking on shore is bod, a heap of stones or rocks is kyerro, a heap of tangles is kest, heavy swell is dawdoswang, a calm spot in the water is a ligny, a boulder on the beach is a klimper, rotting piles of seaweed is a brook, a large rounded rock is a bool. So you know, there’s a lot of words there that are no longer used. Bool I do use but some of the other ones I haven’t used. But I think we’ve lost a lot of rich language up in Orkney especially since, I would say, the 1970s when a lot of incomers came up there. Also a lot of the teachers of course come from various parts of Scotland and England, so people are not speaking broad Orkadian in schools. In fact we didn’t either. I don’t know how we learnt how to read because we have different ways of pronouncing words and different vowel pronunciations.

JR: Were some of these words new to you when you did the recent research?

SN: Yes completely new.

JR: And you hadn’t heard them?

SN: No, I had not heard them, but I just thought they were so descriptive and I think it’s such a shame that we don’t use them anymore. I think you know television and the Internet is, you know, making it even worse because everybody now seems to want to talk like, you know, Californian…

JR: Sound bites? [SN: Yeah] I noticed that you had said, when you were a corresponding with me, that you sometime dream about the quilts.

SN: Yes I do, yes.

JR: Can you tell me more about that?

SN: Well I don’t know how it happens but sometimes when I’m sleeping I have images in my head, of quilts, and it’s a weird. Sometimes by the time morning comes I forget what they look like unless I write them down straight away, but I think if you’re thinking about how you’re going to make a quilt before you go to bed I think it stays in your brain and then your subconscious takes over and you know sometimes the problem’s solved during the night [while laughing].

JR: Do you know how many quilts you’ve made in your quilting career?

SN: No I don’t although my pen friend from New Zealand stayed here last year and I counted about 14 large ones on my bed, but most of the other ones are more wall hangings, door size, to maybe a metre square and whatever size so…

JR: I know that you have made journal quilts and you’ve taken part in the contemporary quilt journal challenge?

SN: Actually I haven’t, no. I never have time. [JR: My mistake] Most of what I do these days is Workshop samples or samples may be for a forthcoming book or for Aurifil Threads. I do a lot of samples for them. A lot of what I do is much smaller these days. I would like to do journal quilts and I remember there was one on circles and I had it all drawn out what I was going to do but I just didn’t have the time. You know, when you’re travelling the country teaching, it’s quite difficult to get a balance of how you are going to use your time because it’s very precious. I thought when I stopped full-time teaching I would have plenty of time to make things, but you find that time is money and you have to pay your bills. So when teaching jobs come along you have to do the teaching jobs to get the money to pay the bills. Then you find you can’t afford the time to spend to make huge quilts, so that’s another reason why I haven’t made huge quilts in the past seven years I couldn’t afford to.

JR: And do you think you have got the balance right?

SN: Well I’m beginning to, in that now I’ve got my teacher’s pension I’ve got a regular income. I’m going to stop travelling the country quite so much. I do have a lot of ideas in my head for more seascape and pictorial quilts. There’s one I want to make to do with my mother and one to do with my father. But it’s about eight years now since they died and this here is actually the first personal one I’ve made since they died. I haven’t really done much to do with Orkney since they died. [JR: Is that the Sea Pinks?] Yes I mean ‘The Sea Pinks of Sandwick’, I feel now I’m ready to do more personal quilts with more stories in them because, what I’ve been doing the last seven or eight years is more patterns.

JR: You said that when you were a little girl you liked to look at books of pictures.

SN: I did yes.

JR: And that you would make up stories. So do you think your quilts have taken that on to another level? You are now using your quilt to visually…?

SN: Yes and also I used to like to listen to stories. The primary teacher at school would read us Enid Blyton stories and that really stimulated my imagination. I like to do things from my imagination and memory rather than, you know, I never sit and do observational drawing. I think I was put off at school because you had to do heaps of still life and I can’t stand sitting around drawing still life’s and things that don’t appeal to me. I wouldn’t mind having a go at going out and painting a landscape. I might eventually go and try painting you know if my eyesight goes or my fingers get arthritis or whatever. I would still do something creative even if it was huge brushes on huge canvases I would be doing something creative. But fabric and thread is my first love.

JR: Can you tell us a bit more about the fabrics you love using?

SN: Well the lady from ‘The Contented Cat’ used to call me the ‘sludgy lady’ because whenever I went to the fairs at Ingleston I would be buying fabrics, greys, beiges, browns mostly collecting fabrics for rocks, and she always had a good stock of them. So when I buy fabrics I tend to buy them because I like them or because I have a seascape or a landscape in mind. But recently with these new modern fabrics with the large scale prints I have been buying some of them as well because I quite like them, they are refreshing in a way. I think for a few years there was nothing fresh. You know you had this Fossil Ferns around for many years and Bali Batiks, all these painterly fabrics. I think it was time for a change and I think we all need to have a change now and again and move on. Certainly the Bali Batiks, the Fossil Ferns are great for landscapes and seascapes but modern quilting being popular now, I think, the more graphic prints are more suitable for that and it’s a different challenge. You know, you’ve got to move with the times, you can’t be stuck in a rut if you have the same colour palette all the time. It’s quite good to force yourself to choose something different for a change. I don’t tend to dye many fabrics because I don’t have the facilities and again it’s a throwback to painting and the messiness of it.

I think there’s plenty of good commercial fabrics out there made by experts. I know City and Guilds were responsible, I think, for introducing dyeing of fabric when the City and Guilds Patchwork and Quilting started. To be perfectly honest a lot of the hand dyed quilts looked not very professionally dyed because they were pretty hit and miss. Whereas if you buy commercial fabrics they are more professional looking.

JR: I suppose if you are free machining you can concentrate your efforts and time experimenting with that?

SN: Yes I buy a lot of self-colours because I do a lot of free machining I tend to, although I buy a lot of patterned fabrics, I tend to go for the plain fabrics if I can, so I can draw on top of them with the needle.

JR: So have you been building up a stash of fabric for a long time Sheena?

SN: Quite a long time yes. I left my previous flat with about four carrier bags, no, I went into my first flat with four carrier bags, I left with I don’t know – maybe 20 bin bags of fabric and now I hate to think what I have. Let me see, as somebody said to me, ‘you’ve reached the sable stage’ S-A-B-L-E, stash above and beyond life expectancy! So because of that and I haven’t got room for any more fabric I now buy things like thread and lace. So that’s my latest hobby collecting bits of lace.

JR: Changing the subject a little bit, I wanted to ask you about your teaching. I know you taught and that was your career. You also enjoyed teaching quilt groups. Is that something you do on a weekly basis?

SN: Well it varies. For the past seven years I did weekly classes locally for units of maybe five weeks at a time and then maybe have a break and then maybe another five weeks. Most of the teaching I do is one day workshops throughout the country. In fact I get most of my work from the South of England and most of the teaching I get is through The Guild. So The Guild has given me a lot as far as teaching is concerned. I’m very grateful for the whole network, you know, as a teacher. You get to meet so many nice people, quilters are really nice people. And because I did Geography as my main subject at college I’ve always liked to travel, even when I was a wee girl going on to my granny’s I like to travel. And I flew for the first time when I was eight, we went to Aberdeen. I’ve always had the travel bug but you know it’s good.

JR: And do you find teaching still enjoyable?

SN: Yes I do. I like to try and get people to do their own designs. A lot of people are frightened of the word ‘design’. But if you give them a kind of menu of things to choose from, it’s a bit like a recipe you know, a bit of this and a bit of that, how about doing this, how about doing that, I think, it’s much more satisfying for them if they can do their own designs. A lot of people do like to copy exactly what you do, but I try and discourage that, I try to get people’s own creativity out. It’s a matter of giving them the tools and encouraging them.

JR: I know that when you worked on your projects in the magazines you always gave thorough instructions and you were very meticulous. Is that how you approach all your quilting projects with that same degree of care?

SN: Well I try, sometimes I kind of step in with size 10 boots and then wish that I had planned it a bit more. I don’t to do a lot of you know drawing and, and that beforehand. I do quick sketches and scale them up very quickly and just get stuck in. I haul out you know all the fabric that I think might be suitable and then gradually reduce the pile until I, you know, arrive at the right colours of fabric. You can have a huge stash of fabric and yet you might not have the right grey. I remember when I went on a course with Michael James at Beamish for five days in 1984. It was on colour. I learnt so much about colour and just how many greys there are for instance. So it’s quite time consuming at the beginning when you’re selecting colours. That’s what takes me the most time is getting the right colours and even when I’ve finished I think ‘I shouldn’t have used that there I should have used the other one’. You know you’re never 100% happy with what you do, you think ‘I wish I done this I wish I’d done that’.

JR: You have lots of patterns and projects and instructions, a huge library, do you think there might be a book in all of that or several books in with that?

SN: Yes hopefully I really would like to do more writing and as I say hopefully I could start with one book and see how I enjoy doing that and then I think I’ve got too many ideas for one book so I would like to do books and make the books kind of self-help books. [JR: like a series of teaching…?] So students can work their way through them, exercises so they can try this and try that. Mostly on machine quilting a lot of people don’t have the confidence, most people don’t know how to use lines and shapes and their own patterns. They tend to go on the Internet and copy what other people do. Whereas I work it out in a very logical manner you know how to go about it. The funny thing is I hate reading instructions but I don’t mind writing instructions.

JR: Luckily you don’t need to do a lot of that [laughter]. I know you are very passionate as a quilter and every day you quilt and create.

SN: Most days but if I’m on the road teaching I can’t or if I’m up in Orkney helping my sister I can’t because I’m doing farm work. But it’s actually quite good to get a break away from it sometimes because when you come back you see things slightly differently and it makes you go off maybe on a different tangent. I mean, even when I was home there in Orkney I was gardening and digging the borders, the hens were scratching as quickly as I could tidy it up, but the light was so spectacular that day. It had been raining and part of the sky was really black, inky and grey and navy blue and yet there were these filters of light coming down shining in the sea so it was almost silver and you know you have to just stand and absorb all that. As my mother said, you know, you always have to take time to stand and look and I think she was quite right. She always used to get onto me when we were out on walks that I was walking too fast, she said ‘take time, stand and look’ and so I remember that. Another thing my granny used to do, was she had a coal fire and we used to sit and we had to imagine what kind of pictures we saw in the fire. And also my mum did the same kind of thing when we were taking in the harvest, you had to wait until there were seven rounds of cutting the oats until we had enough sheaves to build a stook so we used to lie on our backs and look at the clouds and look at shapes in that. In fact one of the quilts I have, a little wall hanging, had cat shapes in the clouds it was one that I did when the three cats who died and I put a cat god up there too, to look after them.

JR: You have got a great imagination. Do you have a lot of friends in the quilting world?

SN: Yes I do. I’ve always had a patchwork house group although I have to say we don’t do much stitching these days it’s more of a ‘grumpy old women’ type meeting. I go to Highland Quilters regularly and I keep in touch with quilters throughout the country, so, yes.

JR: Is your house group just a small group in your home?

SN: Yes there’s four of us.

JR: I know you travel the world to teach and you seem to make lots of lovely friends and connections that way. Do you keep in touch with them after you’ve been to the event or done some training course? Do you keep in touch on the Internet ?

SN: Yes more so now that there is email. When I was in New Zealand recently I met some really nice people and I’m in touch with a quilter from Canada called Mary Powell whose work I think is just so incredibly different from anything else I’ve seen and we hit it off because we have the same kind of sense of humour. And then my penfriend in Wellington she’s now a quilter as well, so we swap ideas over the internet. I try not to spend too much time on the Internet because you know I’d rather be sewing.

JR: Which brings me to a question I was going to ask you about, what you have in progress at the moment?

SN: At the moment? Well let me think, I’ve got a sample for a class called Hand Quilted Ridged Winter Landscape. I’m about to draw out another sample for Aurifil. I’m blending stranded cottons in ten different colours in one step, colour blends on little circles. I’ve got a quilt that I pieced last year with colours to go with the Zingy collection for Aurifil, a double bed size. It’s now ready to tack together to quilt. I’ve got another one that I made last year that Alex Veronelli decided he wanted, rather than the snowscape I made for him and it was part of a series of four so, before I sent it off to him, I made another one very similar and its ready to quilt. And I’ve got two ready to bind and I’ve got another set, it’s a series to do with dancing. Its little stick men that I print with a wine bottle cork and sticks. I did one called ‘Dancing In The Rain’ another one ‘Blue Rain Dance’ and last year I did one called ‘Umbrella Dance’ so now I’ve got one called ‘Square Dance’, ‘Highland Flingers’, ‘Dancing in the Sunset’, ‘Dancing in the Moonlight’ and ‘Dancing in Snow’. So I’ve got three of them ready to quilt as well.

JR: And how would you organise your day and your week to give time to all these projects?

SN: Usually in the morning I like to quilt and I don’t sit for longer than about an hour and a half at a time. So I’ll free motion quilt or walking foot quilt for about an hour and a half, and then I’ll go off and maybe have a cup of coffee and maybe read any mail and then I go back and do another lot so I do that up until half past 12. Now in the winter I’m a bit lazy and only get up at half past nine. So there’s not that many hours before half past 12. Then in the afternoon I generally go out for an hour’s walk at some point and then back in again. Now in the wintertime the light gets bad I tend not to stitch, I tend to stitch straight after lunch and then go for the walk whereas now when the light’s better I’ll go for the walk first and then come back and stitch. So any machining usually ends about half past four and then I start having something to eat for tea about five. At the same time I do my emails around teatime. Then at night time its watching television and doing hand stitching, like putting binding on quilts or doing hand appliqué or embroidery or hand quilting or drawing out the plan or the pattern for transferring onto a quilt. Or drawing patterns, I do a bit of drawing at night.

JR: And then go to bed and dream of quilts?

SN: I try.

JR: We’re coming to the end of the interview, just one thing to close. When will your next exhibition be Sheena, have you got anything in the pipeline?

SN: No, not at the moment no. I had one last year in Luxembourg called ‘Back to Square One’ and I’m still adding to that. I would quite like to have one maybe locally at sometime because I did a PowerPoint presentation called ‘Seasonal Inspirations’ and nobody’s actually seen all that work together you know as a body. Neither have they seen… well you have seen ‘Square One’ in Luxembourg and it could go elsewhere I suppose.

JR: So there’s a book and an exhibition and lots of projects in the pipeline?

SN: Yes there is.

JR: Well you’re a huge inspiration to people and it has been lovely talking to you. Thank you.